The Origins of Cocktail Culture in Germany

The Leipzig publisher Dr. Paul Martin Blüher did not include any recipes in his culinary encyclopaedias, but nevertheless handed down an enormous amount of detailed information on the emerging cocktail culture in Germany. — Blüher’s culinary lexicographical interest in the term “cocktail” reveals its incipient establishment in German gastronomy at the turn of the century. — Blüher also mentions cocktails that are otherwise unknown or that only became known later. — Knowledge in Germany about cocktails was strongly influenced by informants from the USA, who were often of German descent. — In addition to American cocktail books, English publications played an important role in the German reception. — Books by Jerry Thomas, William Terrington, Harry Johnson and William Schmidt could be bought from Blüher in Leipzig. — A complete bar menu from Berlin survived from 1899. — Cocktails have always been expensive in Germany, too.

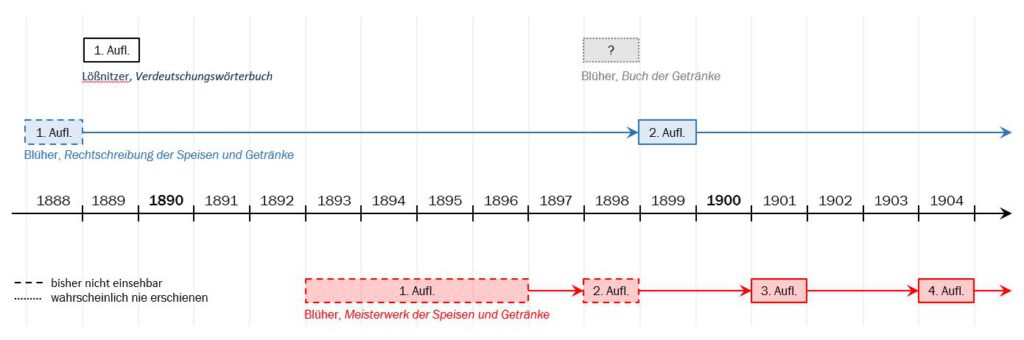

The Leipzig publisher Dr Paul Martin Blüher initially had no particular interest in cocktails – even though a few years later he was to publish one of the first German cocktail books in the form of Carl August Seutter’s “Mixologist”. Blüher’s own publications towards the end of the 19th century were primarily characterised by his efforts to document and catalogue all the terms of solid and liquid culinary arts in their correct form. They thus shed some exciting light on the awakening cocktail culture in Germany. Blüher was obviously more concerned with the orthographical impeccability of menus than with a culturally pessimistic purism of language. In 1888, a year before Lößnitzer’s “Verdeutschungswörterbuch der Fachsprache der Kochkunst und Küche”, on which Blüher had worked [Blüher 1901, 3], he published the “Rechtschreibung der Speisen und Getränke” (“Orthography of Food and Drink”) as, as it says on the title page:

„Zuverlässiges Auskunftsbuch über die im gastwirtschaftlichen Gewerbe, in der Kochkunst, Kunst- und Feinbäckerei, bürgerlichen Küche, Charkuterie, Konserven- und Delikatessen-Branche wie in der Getränkekunde vorkommenden Bezeichnungen zur Aufstellung, Rechtschreibung und zum Verständnis der Speisekarten, Menüs, Weinkarten, Preis-Verzeichnisse, Etiketten usw.“

“Reliable reference book on the terms used in the catering trade, in cookery, art and fine bakery, bourgeois cuisine, charcuterie, canning and delicatessen industry, as well as in beverage science, for the preparation, spelling and understanding of menus, menus, wine lists, price lists, labels, etc.”

Apparently Blüher had filled a gap, so that the book was “within a few months »out of print« (completely sold out)” and so sought after that it was soon traded at collector’s prices [Blüher 1899, 3]. On 392 pages, countless entries, grouped into thematic sections, are juxtaposed in their correct German, English and French names. Section III on drinks, which deals mainly with wine, has a two-page appendix on “American drinks”. This presents the preparation of 15 drinks, including Brandy Smash, Champagne and Sherry Cobbler, Gin Cocktail, Gin Sling and Knickerbocker.[1] Unfortunately, it has not yet been possible to consult a copy, as apparently what Blüher postulated about his “Rechtschreibung” without false modesty also applies to the few libraries that own it: “Whoever has the book just holds on to it as an inalienable treasure” [Blüher 1899, 3]. Fortunately, the second edition of 1899 is much better available and – as will be shown – much more fruitful for the beginnings of cocktail culture in Germany. But first, another book came into being.

Herr Blüher from Leipzig and his Meisterwerk

In fact, Blüher set to work immediately after the success of the first edition, but did not want to publish a mere reprint, but rather to be even more complete and even more correct. During the revision, change in conception and scope arose, so that between 1893 and 1896, in several deliveries, a voluminous directory of almost 15,000 dishes and beverages was produced on more than 2,000 book pages. This was not a second edition, but a work in its own right, which was consequently given its own new title: “Meisterwerk der Speisen und Getränke” (“Masterpiece of Food and Drink”). All the dishes and drinks that Blüher was able to track down together with a whole staff of co-authors were “systematically arranged according to their origin, according to the basic ingredients in groups that belong together” [Blüher 1899, 4].

Exclusively devoted to beverages is the second part of the second volume of the “Meisterwerk“ as the “Most Reliable and Greatest Specialised Work”. The largest space is taken up by wines from all over the world, followed by spirits, beers and mineral waters. Of course, of particular interest here is section VII. on “Bowls, punches, American drinks (mixed drinks)” with over 1,500 entries[2] (which will be discussed later). Even though only the names of the drinks are listed here and roughly sorted by genre, some information can be drawn from it.

Despite the declared claim of “Verdeutschung” (“Germanisation”), Blüher’s “Meisterwerk“ was refreshingly international [Blüher 1901, 3]. Thus, among his closest collaborators was his stepson Curt Zeiler, whose early death he had to mourn in 1897. Zeiler had lived for seven years in the United States, where he had “acquired the most thorough knowledge of English” [Blüher 1901, 3]. It stands to reason that after his return to Leipzig, Zeiler assisted his stepfather in writing “letters to various authorities, often in the most distant countries, even California and Australia” for research purposes [Blüher 1901, 5].

Herr Husmann from Brandenburg

Blüher mentions one of his contacts in California, George Husmann, by name in the preface of the beverage volume [Blüher 1901, 1529]. Because a great deal is known about his life and work, which throws an interesting light on the connections between Germany and the United States in the 19th century, Husmann’s biography will be briefly discussed: Born in Meyenburg in Brandenburg in 1827, he came to the United States from Wilhelmshaven with his parents when he was ten years old. The family first moved to St. Louis, a stronghold of German emigrants (where they possibly already had relatives or friends). In 1839, the family settled in Hermann, Missouri, a place that had been founded two years earlier by the “German Settlement Society of Philadelphia” east of St. Louis in what is still called “Rhineland”.[3] The G. Husmann Wine Co. still has its headquarters where the boy from Brandenburg planted his first vines.

After the Civil War, in which he, like most German-Americans, had fought on the Union side for the abolition of slavery, he published the successful reference book “Cultivation of the Native Grape and Manufacture of American Wines” [Husmann 1866] in 1866, which helped him to become a renowned expert on viticulture in America. After years of mainly academic activity, Husmann was invited in 1881 to become manager of Talcoa Vineyards in Napa, California, where his wines achieved great success. Until his death in Napa in 1902, he published further specialist articles, including the standard work of his time “Grape Culture and Wine Making in California” [Husmann 1888].

As far as American wines were concerned, Blüher was obviously well advised. In the preface to the 2nd edition of the “Meisterwerk“, dated July 1897, he also announced a separate beverage book that was being written with American help [Blüher 1901, 6]:

“In addition, the manuscript of the largest “Book of Beverages”, written by us, checked and perfected by a proven expert in America, with about 1,200 proven preparation instructions, is already almost ready for printing and will appear […] (about the year 1898).”

However, the work seems never to have been published. There is no trace of a “Book of Beverages” under Blüher’s aegis and the beverage section of the “Meisterwerk” does not contain any “preparation instructions” (we would say: specs) even in the fourth edition in 1904.

Herr Brehme from Brooklyn

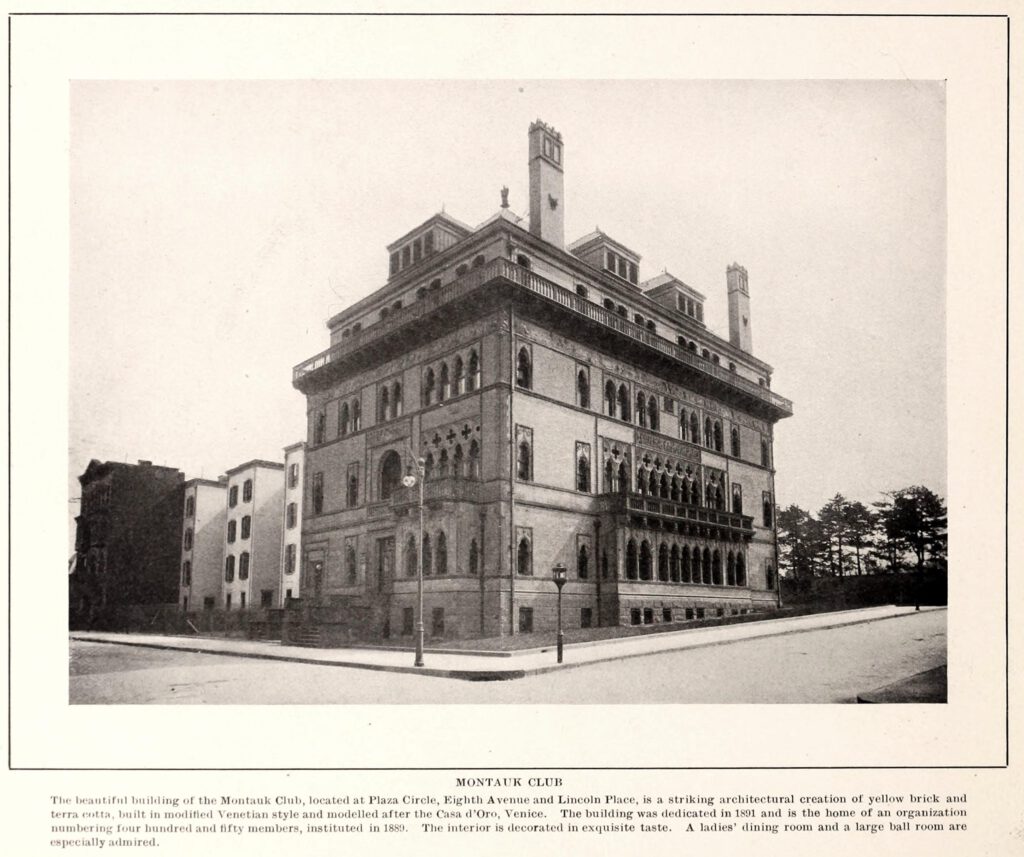

Blüher, however, had American help for the chapter on mixed drinks, which is the focus of the considerations here. The introduction was written by Gustav Brehme, the first regular club manager of the Montauk Club in Brooklyn, New York, founded in 1889. Brehme had previously worked as a steward at the renowned Hamilton Club, also in Brooklyn. With a handsome salary, his new position at the Montauk Club gave him the authority to purchase the club’s wine and spirits on his own responsibility.

In 1892, he was arrested for assaulting a club lift bellboy who, in Brehme’s opinion, had taken too long a lunch break. For the club, the gaffe was apparently no more than a peccadillo, because the position of club manager was not filled by someone else. While the Montauk Club is still active today at 25, 8th Avenue, Brehme took his hat in 1902 to open a restaurant in Manhattan with the Montauk Club’s chef (a fact apparently unknown to Blüher when the 4th edition of the “Meisterwerk” was published in 1904). Gustav Brehme died in 1913. On the Montauk Club’s website, from which most of this information comes, his first name is rendered as “Gustave”.[4] However, the spelling of the meticulous contemporary Blüher is to be trusted more, so that Herr Brehme may have been one of the many German immigrants in New York. In conclusion, it is at least within the realm of possibility that the introduction is not a translation from English, but was written in Brehme’s mother tongue.

Compared to Manhattan, Brooklyn was not the epicentre of cocktail culture at the end of the 19th century, but the impressions and knowledge are likely to have been much more immediate and at least partly the result of personal experience and tasting. After a genuinely endeavouring arc to Schiller, Homer as well as to Renaissance scholars, the punch is presented as a precursor of the contemporary American mixed drink from the 17th century. Finally, Brehme gets to the heart of the matter [Blüher 1901, 1881 f.]:

The allocation of drinks to men and women seems anachronistic to a modern reading public – which it undoubtedly is. However, the reference to alcohol consumption by children is altogether disconcerting. In view of a growing temperance movement on the threshold of the 20th century, which not only in the USA tirelessly and with increasing social penetration drew attention to the (hitherto known) dangers of alcohol, Brehme might also have caused surprise among his contemporaries. While he may have been aware that he was writing for a reading public in Germany, it remains unclear whether he had German or American conditions in mind when he wrote about the ubiquity of the American bar. In fact, it can be shown that from 1899 at the latest, American bars sprang up in many German cities, mostly integrated into hotels, as one would expect, but occasionally also appearing as part of trade fairs or as independent businesses. The statement that such bars could be found “at most places of amusement and bathing” cannot be substantiated. Brehme could have had places like Coney Island in mind in America, which had flourished as an entertainment area in the 1870s. Finally, in the quoted passage, he seems to assume that American bars are mainly frequented by Americans, but that they are also attractive to “members of other cultures”. Whether you set the scenario in Germany or in the USA, it presupposes a lively, international “tourist traffic”. This was perhaps true of Berlin and Hamburg, but probably not of cities like Aachen or Magdeburg. Some of the comment about the ubiquity of the American Bar therefore unfortunately remains in the dark.

Brehme goes on to talk about the actual drinks, which he classifies [Blüher 1901, 1882]:

This is followed by an exemplary stringing together of the names of 52 “short” and 46 “long drinks”, all of which can be found in the actual lexicographical part of the chapter. Even Brehme does not succeed in creating a fully conclusive classification of all American drinks, so that he alternatively offers “several groups, differentiated by their method of preparation”, which essentially correspond to the expected: sours, cocktails, juleps, punches, cobblers, fizzes, noggs and flips, as well as various drinks. For each group, the most important ingredients and characteristics of their preparation are presented below, so also for the cocktail [Blüher 1901, 1882]:

The label “Mixed drink par excellence” is testimony to the special popularity that the cocktail achieved in America in the 19th century and which contributed to “cocktail” eventually becoming a generic term. The following sentence, which gives the words “to fortify the inner man” in English, suggests that Brehme wrote his introduction in German, as it would not be in keeping with Blüher’s passionate meticulousness to leave a half-sentence untranslated simply because it offers difficulties of understanding. It is a garbled quotation from the Englishman William Terrington from his “Cooling Cups and Dainty Drinks” [Terrington 1869, 190]:

„COCKTAILS are compounds very much used by »early birds« to fortify the inner man, and by those who like their consolations hot and strong.“

It’s a well-known fact that cocktails were considered a morning drink in their early days. Fortunately, they haven’t stuck with it, because morning drinking has fallen into a bit of disrepute after all (perhaps for good reasons). To make the phrase not sound quite so esoteric, it is important to know that the “inner man” in British English can refer to the stomach with a wink. The medicinal effect that alcoholic drinks – especially those with bitters – were said to have clearly resonates here. That Brehme quotes from Terrington’s book is remarkable in several respects. Since nothing has been found out about the author of “Cooling Cups” to date, it is mostly assumed that it is a pseudonym. A short newspaper note from the year of publication[5] suggests that the book may have been part of a marketing campaign by the Wenham Lake Ice Co. from Massachusetts, which wanted to use it to boost its business in Europe. Terrington devotes an entire section of his book to the use of ice [Terrington 1869, 124 ff]. Essentially, he had wanted to write about cups, a popular category of drink, especially in England, that is closely related to punch. In the preface, the author reveals that the work on the book led him to write a more comprehensive account, so that modern American drinks – such as cocktails – also found their way into the publication [Terrington 1869, iii f.]. Accordingly, drinks of American origin were marked with an “(A)” in the table of contents, English drinks with an “(E)”. The book was published by Routledge, which, in addition to its headquarters in London, had a second office in New York since 1854. So it is easily plausible that the club manager of the Montauk in Brooklyn could have had the British bar book in his hands. That he quoted from it to explain the American cocktail to a German reading public is perhaps surprising.

The reference to the developed individuality of the cocktails, each of which formed the identity of the bars and the bartenders in America, sounds amazingly current to our present: “Each is proud of his own peculiarities, and each believes that his composition is the most excellent.” One can only hope that the peculiarities of the drinks and not those of the bartenders are meant. The fact that the reference to these statements is so easy to make is due to two things: On the one hand, the changeability and openness to creative design have always been the recipe for success (sic) of the cocktail. Secondly, the cocktail renaissance of the last few decades has led to a return to precisely this attitude: the guest benefits from competition, which leads to ever better drinks. Ideally, anyway.

Brehme’s instructions for making a cocktail (with which he does not follow Terrington[6]) are not to be contradicted in principle, only the swirling sounds like more agitation in the glass than the bar spoon moved briskly but constantly in a circle should produce – since one wants to avoid aeration of the shake. In any case, apart from Harry Johnson, no one in German should have given such a useful instruction at that time. For Brehme, cocktails are exclusively stirred drinks; he assigns the shaker to sours, fizzes, noggs and flips. The presence of liquors in Brehme’s description may be due to the fact that the development towards more complex recipes and a broader understanding of the term was already taking place in the USA. However, he still felt compelled to name a catch-all category “Various drinks” [Blüher 1901, 1883]:

The similarity to cocktails is easy to understand, as Brehme unwittingly gives a description of today’s broad understanding of cocktails in this concluding paragraph of his introduction. The steward of the Montauk Club in Brooklyn has otherwise not made it into mixographic (or potographic) literature to date and will undoubtedly not be counted among the greats. However, Blüher had found a reliable guarantor for his “Meisterwerk”, who provided the gastronomic expert audience with well-founded insights into the matter. It is conceivable that the announced “Book of Beverages” was to be written with Brehme’s help. Perhaps Blüher wanted to get authentic “preparation instructions” from him, which might then have led to the first German cocktail book. The three pages of introduction reveal potential, but these considerations must remain speculation. In 1909, Carl August Seutter was to be able to fulfil the promise in Blüher’s publishing house [Seutter 1909].

Cocktails from Manhattan, London, and Lima

What follows Brehme’s introduction are eleven book pages, each with three columns offering about 1,500 names of drinks that fall under the heading “Bowls, punches, American drinks etc.”. In addition to the announced 34 Juleps, about 290 Punches, 16 Juleps, 15 Fizzes, five Noggs and 21 Flips, there are Crustas, Daisies, Fixes, Pick-Me-Ups, Skins, Slings and Smashes. The 42 cocktails listed below are exemplarily examined [Blüher 1901, 1885 f.]:

Cocktail.

— absinthe-.

— anglers’.

— Athletic club-.

— bitter-sweet.

— Bombay-.

— bourbon-.

— brandy-.

— ” , fancy.

— ” , improved.

— calisaya-.

— champagne-.

— Chinese.

— cider- or cyder-.

— club-.

— coffee-.

— Curlier-Courvoisier-.

— East India-.

— electrical.

— gin-.

— Holland gin-.

— gin-, improved.

— old Tom gin-.

— Hoffman House-.

— Japanese.

— Jersey-.

— Manhattan.

— ” , fancy.

— Martinez-.

— Martini-, engl. (St.) Martin’s.

— morning glory-.

— noyau-.

— old man’s.

— Peruvian.

— Riding club-.

— rye-.

— Saratoga-.

— soda-.

— south-coast-.

— vermouth-.

— ” , fancy.

— whisky-.

— Yale-.

If you take a closer look at the compilation, it reveals which cocktail books it was probably based on: 23 of the drinks can be found in the 1887 edition of “American and Other Drinks”, published by the American bartender Charlie Paul after he moved to England. Among them are telltale names not found in other books of the time, such as the “Anglers’ Cocktail”, the “Bombay Cocktail”, the “Chinese Cocktail”, the “Noyeau Cocktail” [sic] and the “South Coast Cocktail”. 19 drinks are found in George Kappeler [Daun 2022b, 90-93], another emigrant in the States with a German or, more likely, Swiss-German name. The first edition of his “Modern American Drinks” from 1895 is also betrayed by drinks that are not found elsewhere: the “Yale Cocktail”, the “Calasaya Cocktail” [sic] and the “Riding Club Cocktail”, which is also prepared with Calisaya, according to David Wondrich an aromatized Spanish wine [Wondrich 2015, 282]. The fact that the Latin name of the so-called real cinchona tree is Cinchona calisaya could indicate its use and thus a nice bitter note.[7] The extraction of quinine had gained new momentum after the British-born alpaca farmer Charles Ledger from Peru was able to procure under dramatic circumstances seeds of a particularly quinine-containing subspecies of Chinchona calisaya from Bolivia in 1865, which were subsequently shipped to London. However, it was Dutch merchants who started the systematic cultivation of Chinchona calisaya ledgeriana in Java in the 1870s.[8] The agricultural innovation caused a sensation among experts, so that it would at least fit well into the time if Chinchona bark was actually meant here.

The five cocktails that are not to be found in the books of the time deserve special attention. It should be taken into account that especially in the first half of the 19th century, before the first cocktail books were published, the recipes of the novel lifestyle drinks were mainly printed in daily newspapers and magazines [Haigh 2020, 342]. Certainly not every archive treasure has been unearthed yet.

But first to the “Athletic club cocktail”: the name brings to mind the Detroit Athletic Club (DAC), where the famous Last Word was invented on the initiative of a certain Frank Fogarty [Saucier 1951, 151], a potent mixture that Martin Stein has called a “liquid Wolpertinger” [Stein 2019], consisting of equal parts of dry gin, maraschino, green chartreuse and lime juice. The only problem with this is that the drink can only be proven in 1915/16 [Haigh 2020, 93; Wondrich 2015, 331] and that it actually always kept its Last Word name. It is only with the cocktail renaissance of the last two decades that variations of the Last Word have emerged that carry the reference to the DAC in their name, for example the East Village Athletic Club Cocktail, which was first offered in 2008 at the PDT Bar in New York [Zimmermann 2018], or the Detroit Athletic Club Cocktail from 2010, which originated in Colorado, but whose creator Donovan Sornig grew up in the area of the actual clubhouse of the DAC at 241 Madison St in Detroit.[9]

The “Curlier-Courvoisier cocktail” bears Courvoisier in its name, one of the great cognac houses after Hennessy, Martell and Rémy Martin. From 1796, Emmanuel Courvoisier was involved in a wine and spirits business outside Paris before founding the Maison Courvoisier in Jarnac in the Charente département in 1828. When his son and successor Félix Couvoisier died childless in 1866, his nephews Félix and Jules Curlier took over the business.[10] The brothers used both family names on the labels, so that the “Curlier-Courvoisier cocktail” was presumably simply based on Cognac from the house of Courvoisier. Intact examples of “Courvoisier & Curlier Cognac” with an “Old Cognac” bottling from 1789 already fetched prices in the low six-figure range. Since the cognac contained must have been made from wine that was at least 70 years old when the Curlier brothers brought it to market, the bottling will not have been a bargain when it was released. What exactly lies behind the “Curlier-Courvoisier cocktail” remains a mystery for the moment. Possibly it was simply a brandy cocktail as a call drink, i.e. using a specific spirit.

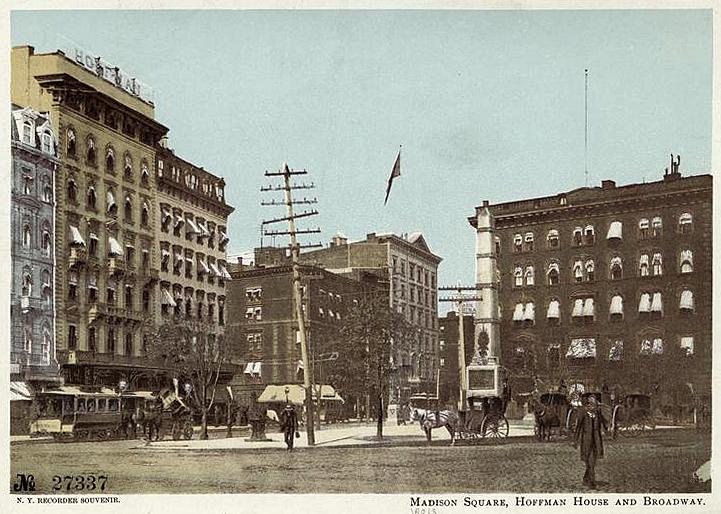

The picture of what belongs in a “Hoffman House cocktail” is much clearer: Plymouth gin, dry vermouth, orange bitters and a lemon zest. Opened in 1864, the Hoffman House Hotel on Madison Park, 25th Street on Broadway (200 metres next to the Flatiron Building built in 1902), with its barroom was one of the first addresses of the golden cocktail era in New York [Wondrich 2015, 54]. Its otherwise unknown head bartender Charles S. Mahoney published the “Hoffman House Bartender’s Guide” in 1905, which was reprinted several times – but the book does not contain a “Hoffman House Cocktail”. We first encounter the recipe in Harry Craddock’s “Savoy Cocktail Book” of 1930, which is no doubt connected to the fact that the latter worked at the Hoffman House from 1912 to 1915 before coming to London [Miller & Brown 2013, 116 f.]. Nevertheless, the drink seems to have been popular already in the 1880s [Wondrich 2005, 78], so that the mention in a Leipzig encyclopaedia of 1901 supports the impression of a certain continuity and popularity.

As for the “old man’s cocktail”, one could see the case similarly, since it was not until 1930 that the recipe for an “old man cocktail” made of anisette, blended scotch, red vermouth and orange zest appeared in “The Home Bartender’s Guide and Song Book” by Charlie Roe and Jim Schwenck. The Prohibition-era recipe calls for Usher’s Green Stripe, which is no longer available today. Which is interesting in that Andrew Usher and his son Andrew Jr. are credited with inventing whisky blending in 1853.[11] Anisette can refer to various aniseed-based spirits from light, sweet liqueurs to pastis. The most common is Marie Brizard’s Anisette, which has been produced in France since the 18th century. What speaks against the fact that we have here a 30-year older record of this cocktail is not so much the fact that in Blüher’s case the name is formed with the possessive “‘s” instead of simply “Old Man”, but rather that the name – in whatever spelling – is far less specific than “Hoffman House” and is still used again and again in various variations for cocktail names. Moreover, Roe and Schwenck attribute their “Old Man” to a head waiter named C. Pasquil from the north of France, who sent in the recipe [Roe & Schwenck 1930, 53]:

„Mr. C. Pasquil, head waiter at the Grand Hotel de la Paix, Albert, Somme, the starting point for visitors to the Battlefields, sends in this one.“

The wording does not exactly suggest that Monsieur Pasquil’s authorship dates back 30 years. Albert was a staging post for British troops in the First World War before the start of the great Battle of the Somme in 1916, and was repeatedly the scene of fighting thereafter, so that it was completely destroyed by the end of the war. In the quoted remark by Roe and Schwenck, American visitors may well be meant, as various US divisions also fought against the Germans on the Somme in the last year of the war. The name of the “Peace Hotel” could indicate that it was named after the war. On the other hand, there is nothing to indicate that Blüher’s “old man’s cocktail” is the same drink.

The “Peruvian Cocktail” also poses a riddle. If one understands the name as an allusion to its ingredients, one will first think of Pisco. From 1822, the Peruvian brandy was available in San Francisco [Wondrich & Rothbaum 2022, 545]. (The Chilean Pisco variant may well be ignored here.) In the form of Pisco Punch, the spirit gained a firm place in the Californian beverage canon from 1864 onwards in the course of the Gold Rush [Wondrich & Rothbaum 2022, 543]. It was mainly through Duncan “Pisco John” Nicol, who was a bartender at the famous Bank Exchange Saloon in San Francisco from 1893 onwards, that the drink achieved fame even beyond the state’s borders [Wondrich & Rothbaum 2022, 545]. The now widespread Pisco Sour can only be documented from 1903 onwards through a brochure by a certain S. E. Ledesma on Creole cuisine.[12] From 1916 onwards, Victor “Gringo” Morris made pisco sour famous with his American Bar in Lima [Wondrich 2015, 119]. In addition to pisco, there is also cañazo, the Peruvians’ own sugar cane liquor, which, however, has not found widespread use beyond the country’s borders to this day [Wondrich & Rothbaum 2022, 544]. The name of the cocktail could also be based on “Peruvian bark”, a term for cinchona bark, which in turn would indicate a bitter note.

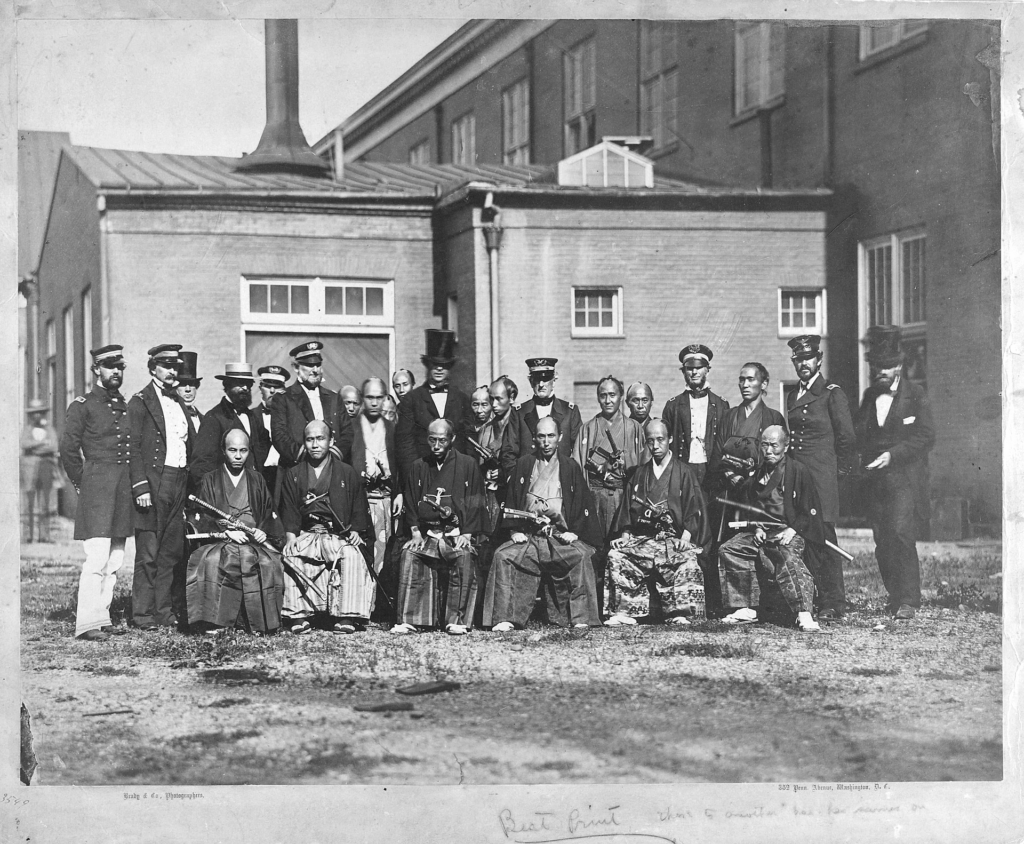

However, all this must remain speculation, because the name of the cocktail can be based on some (perhaps humorous) association that has nothing to do with an origin of its ingredients or the recipe from Peru. Possibly the earliest example of such a cocktail is the Japanese Cocktail with Brandy, Orgeat and Bitters, which was first printed by Jerry Thomas in 1862 [Thomas 1862, 51]. It was probably created on the occasion of the first visit of a Japanese embassy to the USA, whose exotic appearance, including habitus and swords, triggered a veritable Japan hysteria during their two-week stay in New York in June 1860. Since some of the Japanese officers had feasted on cocktails, as the New York Times reported as late as 8 October of that year, it stands to reason that a Japanese Cocktail was also created [Zimmermann 2019; Wondrich & Rothbaum 2022, 391]. In purely physical terms, as David Wondrich says, there’s “nothing Japanese in it”. But as a lieu de mémoire for the Japanese legation in New York, the drink has its place in collective memory (“commemorative cocktail” [Wondrich 2015, 295]).[13] Against this background, any conceivable association may ultimately have led to the name of our “Peruvian Cocktail”.

Another conspicuous feature in Blüher’s list of cocktails should be highlighted: The mention of a Martini cocktail is remarkable in that the now established name form had only emerged in the ten preceding years [Wondrich & Rothbaum 2022, 443]. Obviously, it appears here as a drink in its own right alongside the Martinez cocktail, which is indissolubly linked to the diffuse history of the origin of the most famous of all cocktails. All the more astonishing is Blüher’s addition of “engl. (St.) Martin’s”, which is easy to read over. According to the conception of the book, one would probably have to assume that the Martini is called “St. Martin’s Cocktail” by the English. To date, no further evidence of this can be found. The only reasonably conclusive explanation is that an English equivalent of the Italian surname Martini is given here. St. Martin (yes, the one with the coat) lived in Pavia in northern Italy in his youth before he became Bishop of Tours in 372.[14] The importance that the saint had in the Christian Middle Ages can be seen in the great popularity of his name. Accordingly, the name Martini is the genitive form of (San) Martino, English equivalently: St. Martin’s. The explanation is not satisfactory. Let us therefore return to the drinks in Blüher’s “Meisterwerk” and to the categories into which Gustav Brehme divided them.

The “Various drinks” are spread alphabetically across the columns of the chapter and contain treasures such as the Alabazam, Blue Blazer, Bosom-caresser, John and Tom Collins, Knickerbocker, Prairie Oyster (which was later to become so influential in Germany), Prince of Wales, Stone-fence, Tom and Jerry and even “Jerry Thomas’ own decanter bitters”, with which the name of the professor himself had found its way into this dictionary of Germanization. The recipe can be found as early as 1862 in the first edition of the “Bar Tender’s Guide” and calls for sultanas, cinnamon, snakeroot, lemon, orange, cloves and allspice. The Bitter Truth has had a modern replica in its range for some years. It stands to reason to suspect Brehme’s input behind the selection of drinks in the list. Against this background, however, nothing can be deduced from the compilation as to how well-known any of these drinks were in Germany at the turn of the century.

What has already been indicated in the handsome number of punches in the list continues: In addition to modern American drinks, there are numerous drinks that were familiar to Blüher’s German reading public, e.g. bishops, bowls, coolers, cups, mulled wines, cardinals, possets and sangarees, but also individual favourites from German drink lists of the time such as chaudeau, hippocras, krambambuli, negus and scherbett. Blüher was concerned with completeness, among other things, so that even rather banal-sounding drinks like “orange drink” found their way into the “Meisterwerk”. Nonetheless, the enormous quantity in which American drinks are represented probably indicates that, in Blüher’s estimation, gastronomes in Germany could actually encounter them.

Herr Blüher and his Rechtschreibung

After the planned revision of the “Rechtschreibung der Speisen und Getränke” had, so to speak, escalated into the “Meisterwerk” Blüher nevertheless saw the need to write a second edition of the “Rechtschreibung”, which was finally published in 1899 and – like the “Meisterwerk” – was to undergo several further reprints and reprintings until the 1930s. The first part of the second edition of the book is a short and concise dictionary of culinary and gastronomic terms, which also contains entries such as “American drinks” or “cocktail”: “Kind of americ. mixed drink”, is the brief explanation, and champagne, cider and gin cocktail are listed as examples [Blüher 1899, 69, 106]. Even here, the cocktail has not yet become a generic term, which is underlined by the entry “mixed drinks”: “mixed drinks, esp. the so-called »American« ones, such as cobbler, cocktail, cup, flip, julep, sour etc.”[15]

Herr Schmidt from Hamburg and Herr Johnson from Königsberg

Blüher reveals where he got his knowledge, at least in part, in his extensive and well-structured bibliography – after all, he boasts on another occasion that he has made use of “the existing specialist literature of the whole world” [Blüher 1901, 4]. In addition to German books that do not yet know a cocktail,[16] he refers to a French book and three British books in the section “On drink”, including the work by William Terrington cited above.[17] In particular, the American cocktail books by Jerry Thomas and Harry Johnson as well as both titles by William Schmidt (although Blüher does not realise that “Fancy Drinks and Popular Beverages” is by the same author[18]) are of special interest here. All the titles listed are priced, as Blüher apparently did not only trade in the publications from his own publishing house [Blüher 1901, 764-766].

Thus, here is evidence that some of the most important publications on American and European cocktail culture could be bought in the book city of Leipzig in 1899. Of course, almost nothing can be said about how widely foreign-language reference books circulated, but the question of whether Germans in Wilhelmine times could in principle obtain reliable information about American mixed drinks as well as authentic first-hand cocktail recipes must be answered in the affirmative. Blüher resolutely points out the bilingual nature of Harry Johnson’s book, whose title he erroneously reproduces as “Handbuch der Getränke” (“Handbook of Drinks”), and concludes by adding the laconic remark: “Sehr beliebt.” (“Very popular.”) Unfortunately, this too does not allow any conclusions to be drawn about the actual distribution of the book in Germany, especially as it may be meant that the book was one of the favourites in its American homeland.

Harry Johnson was in Europe at least three times in the years before the publication of the second edition of Blüher’s “Rechtschreibung”, although only about the third stay in 1898 can it be said with certainty that the journey took him to the German homeland [Miller & Brown 2013, 54 f., 60, 82]. From this time on, his first wife Bertha apparently lived permanently in Germany with their two children. It was not until 1903 that Harry’s visits became more regular and from 1909 onwards he also seems to have actively promoted his book [Miller & Brown 2013, 84, 92]. Unfortunately, since the third edition of 1900, this no longer contained a German-language section. English was taught at secondary schools in Germany,[19] but the knowledge of the language was by no means so widespread that a German text would not have helped the sales of the book. The third edition also seems to have been co-published or distributed in London by Stationers’ Hall.[20] It is conceivable, but by no means proven, that he had already been helped by the distribution of remnants of the second edition in Europe. After the First World War was over, Prohibition considerably restricted Johnson’s business activities in the States, so that the European market became more attractive. In 1913, when Prohibitionists had already achieved enormous political influence in the USA, it is reported that he wanted to publish translations in French, German and Dutch, but to all appearances this never materialised [Miller & Brown 2013, 84]. He did not return to the States at last and was buried in 1930 in the Heilig-Kreuz-Kirchhof in Berlin-Tempelhof [Miller & Brown 2013, 93]. There is thus no reliable evidence that Harry Johnson himself was involved in the distribution of his book by Paul Martin Blüher.

Drink menus from Bad Kreuznach and Berlin

A particular stroke of luck for the search for the beginnings of cocktail culture in Germany is the part of the “Rechtschreibung” that is composed of a reproduction of food and drink menus from Blüher’s impressive collection (“probably the largest of its kind”) [Blüher 1899, 447]. Due to his place of activity, the 42 beverage menus form a focus around the geographical centre of Germany. It must be no coincidence that Blüher’s centre of work and life was in the flourishing publishing city of Leipzig, which was relatively close to the cultural metropolises of Dresden and Berlin. Unfortunately, he only mentions the cities where the pubs were located in each case, not the addresses or owners.

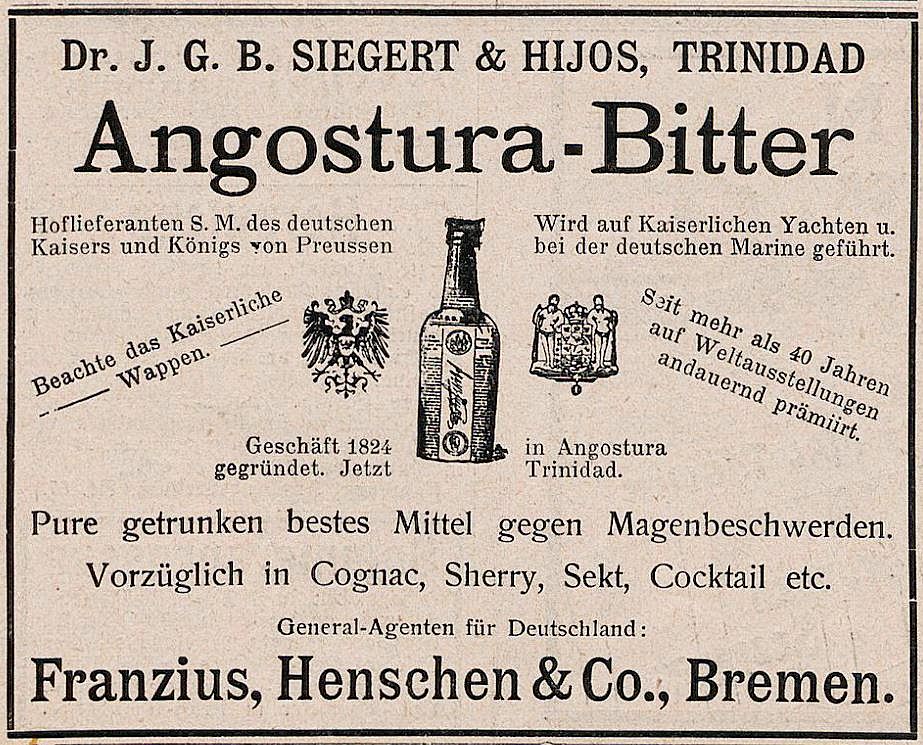

Liqueurs such as yellow and green Chartreuese, Bénédictine, Curaçao or Angostura bitters, which today are only familiar to cocktail aficionados as ingredients of their drinks, are surprisingly regularly found in the menus. Whether in the urban centres or in the “Kaiser-Au” in tranquil Bad Kreuznach [Blüher 1899, 559], people apparently used to drink them straight. While the very idea of ingesting a shot of Angostura causes phantom pain, the exotic elixir was advertised in contemporary newspaper ads, which of course made no secret of its German inventor, Dr Johann Gottlieb Benjamin Siegert.[21]

Some of Blüher’s menus offer champagne and sherry cobblers, while almost every one of them features a selection of punches, always in hot form, often alternatively cold. Likewise, grogs are ubiquitous, with a choice of base spirits usually cognac, rum or arrack. Arrack, originally from India and made from palm or cane sugar juices, which in previous centuries was mainly used as a punch ingredient [Wondrich & Rothbaum 2022, 35-38], is also offered on many menus for pure enjoyment. Today, arrack has almost completely disappeared from the collective consciousness and has only recently been revived in the course of the cocktail renaissance. In the relevant online shops, one finds a handful of different varieties, mostly mediated by Dutch bottlers who distribute products from Indonesia or Sri Lanka.

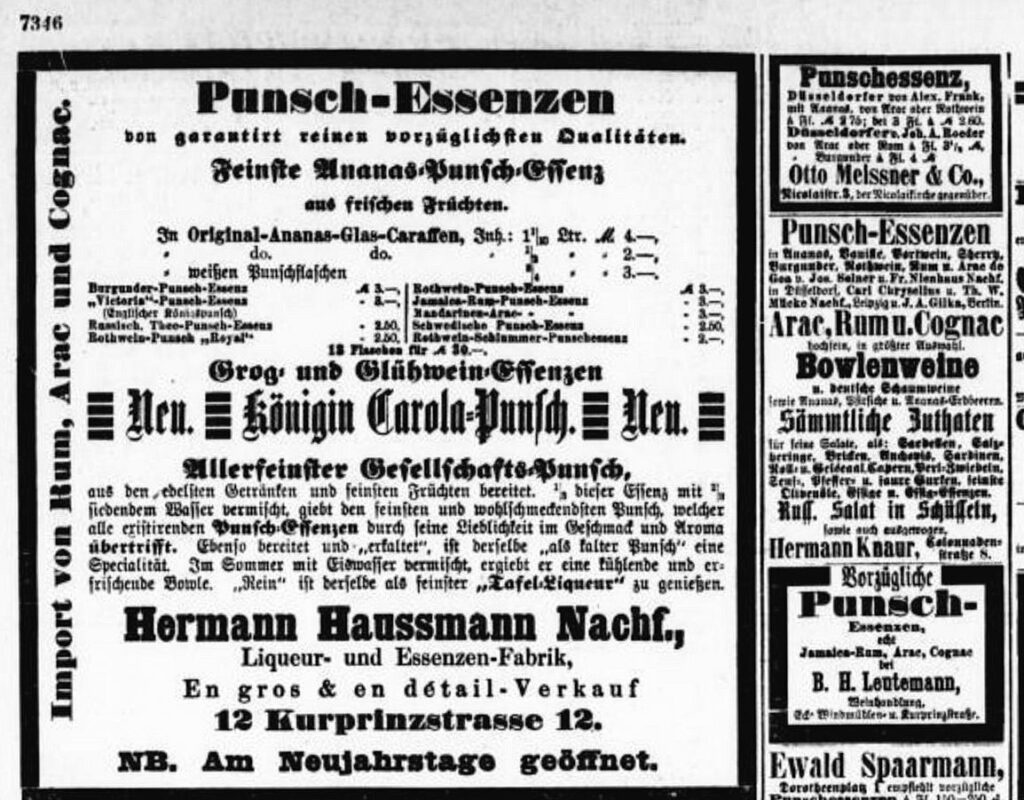

The punches on offer mostly correspond to certain recurring standards, such as “Arrakpunsch” or “Punsch Romaine”. Own creations appear only exceptionally and only in pubs whose drinks menu focuses on punches. An impressive example is Café Bauer in Berlin, which offers a total of 16 different hot and cold punches. A fine reflection of its time here is in particular the “Königin Carola Punsch” (“Queen Carola Punch”), which apparently enjoyed regional popularity at times. It bore the name of Carola of Vasa, who became the last Queen of Saxony with the coronation of her husband Albert in 1873. By that time, the state had already been absorbed into the German Empire under Emperor Wilhelm I. Her duties as queen were therefore of a representative nature on the one hand, and on the other hand she rendered great service to the care of the sick and wounded in Saxony.

What the Queen Carola Punch tasted like or what ingredients it contained unfortunately remains obscure. Apparently, however, it was not something dishonourable for the monarch to have an alcoholic drink named after her. The naming may be understood as a tribute rather than a humorous corruption. It was not uncommon for bridges, schools, ships or the “Carolafelsen” (“Carola rock”), the highest point of the “Affensteine” in Saxon Switzerland, to be named in her honour.[22] Preferably around Christmas time, when it was cold and festive, the Leipzig liqueur and essence factory Hermann Hausmann advertised its “Königin Carola-Punsch-Essenz” bottled for home use in the Leipziger Tageblatt. To illustrate the versatile possibilities of preparation, Hausmann even afforded himself space in the New Year’s Eve issue of 1885 for preparation instructions with the addition of “Allerfeinster Gesellschafts-Punsch” (“Finest society punch”):

“⅓ of this essence mixed with ⅔ boiling water gives the finest and most delicious punch, which surpasses all existing punch essences by its sweetness of taste and aroma. Prepared in the same way and »chilled«, it is a speciality »as a cold punch«. Mixed with ice water in summer, it makes a cooling and refreshing punch. »Pure«, it can be enjoyed as the finest »table liqueur«.”[23]

The product itself was not particularly innovative, because the company had to share the advertising section with numerous suppliers of punch essences. Apparently, there was a market in which they tried to place themselves by offering specialities. In addition to the ingredients, it would be interesting to know whether the Berlin Café Bauer offered a branded product that was mixed in the pub with the Leipzig Pre-Mix as a kind of convenience product, or whether the “Königin Carola Punsch” designated a specific kind of drink that every pub could prepare from scratch. It’s possible, of course, that you found both: “Let’s go to Café Bauer, they still make their own Königin Carola Punsch.”

This brings us back to the drink menus in Blüher’s “Rechtschreibung”. Even though unfortunately no information on the ingredients of the mixed drinks was printed, some information can be drawn from the lists. The prices in particular shed light on the situation around 1899. In most pubs, a glass of beer cost 30 pfennigs and a bottle of Moselle wine could be served at the table for 1.20 marks. This sounds like a land of milk and honey to us, but of course it has to be measured against the value of money at the time. Conversion tables that say, for example, that one mark of the German Empire in 1900 is equivalent to 7.70 euros today do not give a reliable picture, because many factors have to be taken into account in such a comparison.[24] Nevertheless, the prices of the various drinks can be compared well, e.g. a glass of punch cost 50 to 60 pfennigs. A sherry cobbler cost 1 mark and in the champagne version the cobbler even cost 1.50 marks – just as much as a whiskey or brandy cocktail at Café Bauer (where the Queen Carola punch cost a proud -.75 pfennigs).

Among the establishments whose cards Blüher has printed, there are for the most part no milestones for the history of cocktail culture in Germany. The Theater-Café in Leipzig, which in addition to the usual punches and grogs can at least offer a sherry cobbler for -.75 pfennigs and a champagne cobbler for 1 mark, is unfortunately not to be identified with the American Bar in the Centraltheater Leipzig, which is illustrated in Seutter’s “Mixologist” [Seutter 1909, 3]. The Centraltheater, on whose site the Schauspielhaus has stood since 1957 after it was destroyed in the war in 1943, was only opened in 1902 in a purpose-built building.

While there are various cobblers in six other of the printed menus, only one other establishment besides Café Bauer carries “cocktails”: the Union Bar in Berlin. Here you could get a cocktail for as little as -.75 pfennigs, but also had the option of spending 2 marks on a Prince of Wales. With around 70 mixed drinks, the drinks menu is on a par with many a modern cocktail bar. Sorted by genre, there are eleven cocktails, eight specials (e.g. John Collins, Knickerbocker or Santina’s pousse café), three sours, smashes and lemonades each, five sangarees, cobblers, fizzes and juleps each, nine flips and 14 punches. The names are almost entirely in English and suggest an American influence to us as well as to the contemporary audience.

The bar at Französische Straße 50 was opened in the year Blüher’s “Rechtschreibung” was published. So we look at the hot-off-the-press menu with which the Union Bar presented itself to the Berlin public for the first time. The evaluation of the drinks on offer reveals where the bar manager drew his inspiration from – which points to London as well as New York. Unlike other establishments presented by Blüher, the Union-Bar can be grasped through other sources, including literary ones, so that it is clear that it was an independent bar, subordinate neither to a hotel nor to another restaurant – possibly the first of its kind in Germany. Since there is a lot to say about the Union Bar, a separate post will be dedicated to it in this blog. In any case, Blüher did not take their drinks menu as an opportunity to add drinks from the Union-Bar to the list of drinks in his “Meisterwerk”.

Conclusion

The delight in catalogues, encyclopaedias and lists that speaks of the Prussian civil servant’s soul must also be seen against the background of the great upheavals of the 19th century. In the age of revolutions and industrialisation, the dissolution of the society of castes (“Stände”), in which everyone’s career was determined by their lineage, was replaced by a civil society in which theoretically everyone could achieve something. This gave education a whole new value and the “Bildungsbürgertum” emerged as the educated middle class. In contrast, encrusted social and political structures were seen as closely linked to the traditional European monarchies. People sought to overcome the arbitrariness and self-righteousness of kings and monarchs through a political construct that has endured to this day as a constitutional nation state. The revolutionary phenomena in Germany in the mid-19th century, especially the March Revolution of 1848, did not bring about the desired changes. Nevertheless, none of the German confederations, which usually existed under Prussian or Austrian domination, lasted permanently. Thus, in 1871, in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War, a German Empire was founded under the Kaiser.

Against the backdrop of these experiences and out of a newfound self-image that focused on the nation on the one hand and on education as desirable goods on the other, one must probably also view the works of Paul Martin Bluher. In his lexicographical works on culinary arts, he offers an impressive number of references to cocktails. Although virtually no information is given on recipes, origin or actual use, we are given a glimpse of the awakening cocktail culture in Germany.

[1] Blüher 1888, 137 f. The advertisement of an online antiquarian bookshop contained low-resolution and poor-quality photos of the table of contents, which nevertheless allowed the information given to be deciphered.

[2] That the first edition of 1896 already contained this section with the same title can be seen from the entries in the library catalogues. These also provide the information that the first edition was only seven pages shorter than the second edition of 1898 and the present third edition of 1901. With a total volume of over 2,000 pages, there is a certain probability that Chapter VII was essentially already available in the consultable form of the third edition.

[3] Art. Hermann, Missouri, in: Wikipedia. The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermann,_Missouri, Retrieval on 31.08.2023.

[4] The Montauk Club, 125-Year Milestones, 02.08.2014, https://montaukclub.com/milestones, Retrieval on 27.08.2023.

[5] Naval and Military Gazette, London, 3.7.1869, 10; cf. Wondrich & Rothbaum 2022, 722.

[6] On Terrington’s cocktail recipes cf. Zimmermann 2017; Daun 2022, 94-97.

[7] In any case, the two products available today with the name “Calisaya” are out of the question: a “Vino Aromatizzato alla China” from Piedmont (Rovero) and a cinchona orange liqueur from Oregon (Elixir Craft Spirits).

[8] Art. Charles Ledger, in: Wikipedia. The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Ledger, Retrieval on 27.08.2023.

[9] Art. Detroit Athletic Club, in: Difford’s Guide, https://www.diffordsguide.com/cocktails/recipe/2924/detroit-athletic-club, Retrieval on 27.08.2023.

[10] https://www.courvoisier.com/heritage, Retrieval on 27.08.2023

[11] https://scotchwhisky.com/magazine/whisky-heroes/14768/andrew-and-john-usher/

[12] S. E. Ledesma, Nuevo Manual de Cocina de la Criolla: Comida, 1903

[13] Wondrich 2015, 295. As Armin Zimmermann has shown, however, the cocktail was not invented by Jerry Thomas [Zimmermann 2019]. As far as the collective memory of the Japanese legation is concerned, one will have to assume that the Japanese Cocktail’s organic connection with the event faded with its already moderate popularity. The renewed interest in historical recipes with the cocktail revival makes it a focus point of that memory again from the opposite thrust (as these lines prove).

[14] Sulpicius Severus, Vita Sancti Martini; cf. Otto Hiltbrunner, Martinus 2., in: Der kleine Pauly 3, München: dtv 1979, 1056 f.

[15] Blüher 1899, 193. The examples mentioned are each provided with short entries of their own that refer back to “mixed drinks”.

[16] Titles that are not exclusively about wine or spirits production: Eduard Gressler, Anleitung und Recepte zur Anfertigung aller Arten moussirender Luxusgetränke mittelst selbstentwickelter und flüssiger Kohlensäure, 3. Aufl., Halle: Hofstätter 1891; Anselm Josti, Die Bereitung warmer und kalter Bowlen und punschähnlicher warmer und kalter Getränke, 3. Aufl., Weimar: B. F. Voigt 1885; C. F. B. Schedel, Praktische und bewährte Anweisung zur Destillierkunst und zur Fabrikation der Liköre und Aquavite, der doppelten und einfachen Branntweine, Spirituosen- und Luxus-Getränke, 4. Aufl., Weimar: B. F. Voigt 1852; Charlotte Wagner, Das Buch der Getränke. Gründliche, allgemein faßliche Anleitung zur vorteilhaften Bereitung von 500 warmen und kalten Getränken, wie Kaffee, Thee, Chokolade, Cacao, Punsch, Grog, Bowlen, Maitrank, Kaltschalen, Limonaden, Fruchtsäfte und -Essige, Essenzen, Liqueure, Weine, Gefrornes, Erfrischungen aller Art. Zum Gebrauch für Haushaltungen aller Stände, sowie für Gastwirthe, Conditoren und Restaurateure, 5. Aufl., Berlin: Mode Verlag 1894.

[17] Niels Larsen, Boissons américaines, Paris: Nilsson 1899; William Terrington, Cooling Cups and Danty Drinks, London: Routledge 1869 [Terrington 1869] bzw. 1872; Bacchus & Cordon Bleu, New Guide for the Hotel, Bar, Restaurant and Chef, London: William Nicholson & Sons 1885; Mrs de Salis, Drinks à la Mode. Coups and Drinks of Every Kind for Every Season, London: Longman’s, Green & Co. 1891.

[18] William Schmidt is known to have visited his elderly parents in Hamburg in 1889, when his book was not yet available [Miller & Brown 2013, 24]. The appearance of his books in Blüher’s list cannot therefore be traced back to a personal distribution activity.

[19] Friederike Klippel, Englischlernen im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert. Die Geschichte der Lehrbücher und Unterrichtsmethoden, Münster: Nodus 1994, 287 ff., https://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/8653/1/8653.pdf, Retrieval on 28.08.2023. See also Philip Eins, Vor 125 Jahren. Einwanderungsbehörde auf Ellis Island öffnet, Deutschlandfunk, 01.01.2017, https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/vor-125-jahren-einwanderungsbehoerde-auf-ellis-island-100.html , Retrieval on 28.08.2023.

[20] Johnson 1900, 4. Many thanks to Armin Zimmermann for the kind reference.

[21] I.e. Beiblatt der fliegenden Blätter Nr. 3016, München, 15. Mai 1903, S. 20, URL: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/fb_bb118/0449/image,info, Retrieval on 30.06.2023.

[22] Carola had a special connection to Punch that goes back to the 17th century (but which is likely to be coincidental and unnoticed until now): As a born Princess of Vasa-Holstein-Gottorp, she was a direct descendant of Frederick III of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf, who had sent an embassy to Persia in 1636. The famous earliest information on the composition of punch (“Palepuntzen”) comes from the travelogue of Johann Albrecht von Mandelslo [Ronnenberg 2023].

[23] Leipziger Tageblatt, 31.12.1885, 7346, https://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/300116/10, Retrieval on 29.08.2023

[24] Deutsche Bundesbank, Purchasing power equivalents of historical amounts in German currencies, 15.03.2023, https://www.bundesbank.de/en/statistics/economic-activity-and-prices/-/purchasing-power-equivalents-of-historical-amounts-in-german-currencies-622372, Retrieval on 29.08.2023.

References

Blüher 1888 = Paul Martin Blüher & Paul Petermann, Rechtschreibung der Speisen und Getränke, Leipzig: Blüher 1888.

Blüher 1899 = Paul Martin Blüher, Rechtschreibung der Speisen und Getränke. Alphabetisches Fachlexikon. Französisch-Deutsch-English (und andere Sprachen) (Blühers Sammel-Ausgabe von Gasthaus- und Küchen-Werken, Band 26), 2. Aufl., Leipzig: Paul M. Blüher 1899, https://archive.org/details/b21504696, Retrieval on 29.08.2023.

Blüher 1901 = Paul Martin Blüher, Meisterwerk der Speisen und Getränke. Französisch – Deutsch – Englisch (und andere Sprachen) (Blühers Sammel-Ausgabe von Gasthaus- und Küchen-Werken, Band 22 und 23), 3. Aufl., Leipzig: Paul M. Blüher 1901, https://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/91483/1, Retrieval on 29.08.2023.

Daun 2022a = Gabriel Daun, Back to Basics 2: Cup der guten Hoffnung, in: Mixology. Magazin für Barkultur 2/2022, 94-97.

Daun 2022b = Gabriel Daun, Back to Basics 6: Modern im wahrsten Sinne, in: Mixology. Magazin für Barkultur 6/2022, 90-93.

Haigh 2020 = Ted “Dr. Cocktail” Haigh, Vintage Spirits and Forgotten Cocktails. Prohibition Centennial Edition: From the 1920 Pick-Me-Up to the Zombie and Beyond – 150+ Rediscovered Recipes … With a New Introduction and 66 New Recipes, Beverly, MA: Quarry 2020.

Husmann 1866 = George Husmann, The Cultivation of The Native Grape, and Manufacture of American Wines, New York: Geo. E. Woodward 1866, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/20917, Retrieval on 29.08.2023.

Husmann 1888 = George Husmann, Grape Culture and Wine-Making in California, San Francisco: Payot, Upham & Co. 1888, https://archive.org/details/grapeculturewine01husm, Retrieval on 29.08.2023.

Johnson 1888 = Harry Johnson, New and Improved Illustrated Bartender’s Manual or: Hot to Mix Drinks of the Present Style, New York: Selbstverlag 1888, https://euvs-vintage-cocktail-books.cld.bz/1888-Harry-Johnson-s-new-and-improved-bartender-s-manual-1888, Retrieval on 30.08.2023.

Johnson 1900 = Harry Johnson, Bartender’s Manual or: Hot to Mix Drinks of the Present Style, Revised Edition, New York: Selbstverlag 1900, https://euvs-vintage-cocktail-books.cld.bz/1900-Harry-Johnsons-Bartenders-Manual-Mixellany, Retrieval on 30.08.2023.

Miller & Brown 2013 = Anistatia Miller & Jared Brown, The Deans of Drink, London: Mixellany Ltd. 2013.

Roe & Schwenck 1930 = Charlie Roe & Jim Schwenck, The Home Bartender’s Guide and Song Book, New York: Experimenter Publications 1930, https://euvs-vintage-cocktail-books.cld.bz/1930-The-Home-Bartender-s-Guide-and-Song-Book, Retrieval on 31.08.2023.

Ronnenberg 2023 = Karsten C. Ronnenberg, Palepuntz and Chinese Whispers – Notes on the Early History of Punch, in: Bar-Vademecum. The guide to the HISTORY of mixed drinks, 04.03.2023, https://bar-vademecum.eu/palepuntz-and-chinese-whispers-notes-on-the-early-history-of-punch, Retrieval on 30.08.2023.

Saucier 1951 = Ted Saucier, Bottoms Up, New York: Greystone Press 1951.

Seutter 1909 = Carl August Seutter, Der Mixologist. Illustriertes internationales Getränke-Buch, Leipzig: P. M. Blühers Verlag 1909, https://euvs-vintage-cocktail-books.cld.bz/1909-Der-Mixologist-by-Carl-A-Seutter, Retrieval on 31.08.2023.

Stein 2019 = Martin Stein, Ted Saucier und sein Verdienst um den Last Word, in: Mixology. Magazin für Barkultur, 8. Juni 2019, https://mixology.eu/ted-saucier-bottoms-up-last-word-chartreuse, Retrieval on 16.08.2023.

Terrington 1869 = William Terrington, Cooling Cups and Danty Drinks, London: Routledge 1869, https://euvs-vintage-cocktail-books.cld.bz/1869-Cooling-Cups-and-Dainty-drinks-by-William-Terrington, Retrieval on 31.08.2023.

Thomas 1862 = Jerry Thomas, The Bar-tender’s Guide, and Bon-vivant’s Companion – A Complete Cyclopedia of Plain And Fancy Drinks, New York: Dick & Fitzgerald 1862, https://euvs-vintage-cocktail-books.cld.bz/1862-Bar-Tender-s-Guide-price-1-50-by-Jerry-Thomas, Retrieval on 31.08.2023.

Wondrich 2005 = David Wondrich, Killer Cocktails. An Intoxicating Guide to Sophisticated Drinking, New York: HarperResource 2005.

Wondrich 2015 = David Wondrich, Imbibe! Updated and Revised Edition: From Absinthe Cocktail to Whiskey Smash, a Salute in Stories and Drinks to “Professor” Jerry Thomas, Pioneer of the American Bar, New York: Perigee 2015.

Wondrich & Rothbaum 2022 = David Wondrich & Noah Rothbaum, The Oxford Companion to Spirits & Cocktails, New York: Oxford University Press 2022.

Zimmermann 2017 = Armin Zimmermann, The origin of the cocktail. Part 4: Historically interesting recipes, in: Bar-Vademecum. The guide to the history of mixed drinks, 15.10.2017, https://bar-vademecum.eu/the-origin-of-the-cocktail-part-4-historically-interesting-recipes/, Retrieval on 29.08.2023.

Zimmermann 2018 = Armin Zimmermann, East Village Athletic Club Cocktail, in: Bar-Vademecum. The guide to the history of mixed drinks, 27.05.2018, https://bar-vademecum.eu/east-village-athletic-club-cocktail/, Retrieval on 29.08.2023.

Zimmermann 2019 = Armin Zimmermann, Japanese Cocktail, in: Bar-Vademecum. The guide to the history of mixed drinks, 23.06.2019, https://bar-vademecum.eu/japanese-cocktail/, Retrieval on 23.08.2023.