[German version | List of historical bars]

Contents:

- Part 1: The Führer gives the people of Munich a bar

- Part 2: Karl Heinz Dallinger, the painter of the “Golden Bar”

- For a drink in the “Führerbau”

- Decorator of power

- A cocktail shaker for Siemens: Dallinger after 1945

- Part 3: The “Golden Bar” during and after the war

- Cocktails in Hitler’s temple of art?

- Americans, carnivalists and critical deconstruction

- The Goldene Bar today and the legacy from back then

- Abbreviated references

Part 1: The Führer gives the people of Munich a bar

[Estimated reading duration: 30 minutes]

On Sunday 18 July 1937, Adolf Hitler opened a bar in Munich.

At least he inaugurated the Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art), a personal prestige project,[1] which was designed with a bar for visitors. Today, the building is simply called Haus der Kunst (House of Art), without the German, and serves as an art gallery for modern art from all over the world. The bar was given a new lease of life in 2010 and has since achieved well-deserved fame far beyond Germany’s borders with its bar manager Klaus St. Rainer. The Goldene Bar, as it is officially known today, was given this name »Golden Bar« by contemporaries soon after it opened.[2] The name is derived from the murals by Munich artist Karl Heinz Dallinger, which depict various wine and spirits production regions from around the world on a gold background. The illustrated maps bathe the room in a warm, almost magical light.[3]

How can this display of cosmopolitanism in the murals be reconciled with National Socialist ideology? Did the artist create harmless decoration in the highly politicised context of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst? Was Dallinger an apolitical artist? Did the bar slip under the radar of those in power or was it a natural part of it? What can be deduced from this for the history of American-influenced cocktail and bar culture in the Third Reich? How can the continuities and ruptures between the original museum bar and its current successor be categorised? In order to approach these questions, we must first consider Adolf Hitler’s relationship to the visual arts in general and to the Haus der Deutschen Kunst in Munich in particular.

Hitler and art

It is well known that paintings were one of Adolf Hitler’s personal passions.[4] Even as a child, he had allegedly wanted to become a painter himself,[5] but was rejected twice at the Vienna Academy, in 1907 in the second round and in 1908 in the first. He used his own failure as an 18 and 19-year-old at the traditional state institutions to stage himself as an unrecognised genius throughout his life.[6] After being rejected by the academy, which he described as highly disgraceful, the “wannabe artist” kept his head above water for a while in Vienna with postcard watercolours based on 19th century paintings[7] – products that he had bought up by party functionaries in later years because their inferior quality did not fit in with the image of the “genius” Adolf Hitler.[8] When he came to Munich in 1913, he developed a close connection to the city on the Isar, which drew him into art circles in the period after the war. He found friends and mentors in the publisher couple Hugo and Elsa Bruckmann. Their nationalist and anti-semitic world view was a decisive commonality.[9]

Hitler’s preference was for German (or what he considered to be German) painters of the 19th century, with representatives such as Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), Carl Spitzweg (1808-1885), Anselm Feuerbach (1829-1880), Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901) and Adolph von Menzel (1815-1905). As soon as his means allowed, he began collecting originals in 1929.[10] At first he bought legally. As his power grew, he also enriched himself by expropriating and looting the collections of expelled or murdered collectors, primarily of Jewish faith.[11] From 1938 until his suicide in the Führerbunker in April 1945, Hitler planned a huge “Führer Museum” for his favourite city of Linz on the Danube, for which he had more than a thousand important works of art history assembled over the course of time.[12] He had public representative buildings such as the Führer’s headquarters in Berlin, but also more or less private places such as the Berghof on the Obersalzberg near Berchtesgaden, lavishly decorated with original paintings. The choice of artists and subjects always emphasised the political and representative function of the respective location. Even superficially decorative art was appropriated as a programmatic illustration of the Nazi ideology centred around the person of the “Führer”.[13]

Hitler’s taste and understanding of art were quite conservative. “Art had no effect on Hitler in the sense of ennobling him; his ability to enjoy art did not form the kind of humanity that idealistic art philosophy taught and teaches.”[14] He loved genre pieces dripping with homeland romanticism that depicted the idyll of a simple life.[15] The “Führer” was limited to objective and naturalistic painting, which had a certain pathos and, in his opinion, demonstrated the creative power of the “Germanic race”.

Impressionism and the development towards abstract painting, which had characterised the artistic avant-garde since the late 19th century, were repugnant to him. Progressive German artists of the time in particular were ostracised as inferior, un-German and Jewish. The “»art lover« Hitler hated modernism to the core – the Third Reich had committed itself to being anti-modern as far as its art was concerned.”[16] This was accompanied by reprisals, bans and persecution from 1933 onwards.[17] The Nazis also waged their “relentless war of purge”[18] by dismantling the disapproved art, most famously through the “Entartete Kunst” (Degenerate Art) exhibition, which opened its doors in the Hofgarten Arcades, 300 metres away, one day after the opening of the House of German Art.[19]

The House of German Art

Although the young Nazi state was able to build ideologically on the art of the 19th century by reinterpreting and distorting history, it had no traditions of its own or genuinely National Socialist art to show for the time being.[20] Shortly after coming to power in 1933, Hitler had announced a four-year plan against which he wanted his successes to be measured. 1937 was therefore an important year for the regime and the establishment of its rule. A large exhibition was opened in Berlin with a Hitler quote as its title: “Give me four years” was a self-congratulation of the “Führer” and the Nazi regime. In the field of art, however, the achievements of the young state were not shown on the Spree, but on the Isar, in the “Capital of German Art”. Hitler had given his adopted hometown of Munich this honorary title for the first time in his speech at the groundbreaking ceremony of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst on 15 October 1933.[21] From 1935, the National Socialists officially named the city, which quickly became a stronghold for anti-democratic and anti-Semitic right-wingers after the end of the war in 1918, the “Capital of the Movement”.[22] The first representative buildings of the regime were built here, such as the “Temple of Honour” for the dead Nazi putschists in 1935 or the “Führerbau” as Hitler’s workplace in 1937. The first large, completed building project was the Haus der Deutschen Kunst in Prinzregentenstraße at the foot of the English Garden.

The design for this “temple of art“[23] came from Paul Ludwig Troost, in whom Hitler found his favourite architect and confidant early on after meeting him at the Bruckmanns in 1930.[24] Troost knew how to mould Hitler’s penchant for monumentality and pathos into clear architectural forms,[25] which looked like an adaptation of Greek antiquity with the modern stylistic devices and forms of New Objectivity (which the Nazis actually hated). The Haus der Deutschen Kunst, this 175 metre long box with its seemingly endless columned front, is a prototype of fascist neoclassicism. Contemporaries mockingly remarked on the stylistic influence of luxury steamers, which Troost had previously been involved in designing.[26] In the Munich vernacular, the building was ridiculed as a “white sausage temple”.[27] However, the architect died in 1934, so that his widow Gerdy Troost, who continued the “Atelier Troost” together with Leonhard Gall, finalised the project in close consultation with Hitler. “The Führer’s buildings are the witnesses of the ideological turning point of our time,” she enthused in 1938, “They are National Socialism in construction.”[28] The financing of the building offered rich industrialists the opportunity to make generous donations to raise the construction costs of 4.6 million Reichsmarks.[29] [In this respect, the title of this article is factually incorrect. It alludes to the unpublished propaganda film “Der Führer schenkt den Juden eine Stadt” (The Führer gives the Jews a city) from 1944, in which the Nazi regime wanted to sell the murder of millions of people as an example of National Socialist generosity and humanity with the help of the showcase concentration camp Theresienstadt, now Terezín in the Czech Republic.[30]]

The House of German Art was inaugurated by Adolf Hitler in a ceremony on 18 July 1937, the Day of German Art.[31] On display were around 500 paintings, prints, sculptures and tapestries by contemporary German artists who enjoyed the approval of the regime and the “Führer” in particular.[32] However, the place was fundamentally different from a conventional museum, as most of the exhibited artworks were for sale – and were eagerly bought. The annual Großen Deutschen Kunstausstellungen (GDK – Great German Art Exhibitions) were therefore more like art fairs.[33] Sabine Brantl, head archivist at the museum since 2005, has convincingly traced how the business functioned, who the buyers were and what sums of money were raised. Right at the forefront – along with other big names of the Nazi regime – was Hitler himself.[34] The art on display was part of the new state’s propaganda and self-presentation. According to the motto “Art for all“,[35] excursions to Munich were organised throughout the Reich by Nazi organisations. A visit to the Haus der Deutschen Kunst was often a compulsory programme for school classes. With the outbreak of war, affordable museum visits offered the population a welcome change and the reassuring appearance of normality.[36] In this way, “massive numbers of people who did not usually go to museums and exhibitions were reached.”[37] The GDK achieved visitor numbers that other museums could only dream of.

The “Golden Bar” 1937

The physical well-being of the travelling masses was also taken care of: the GDK brochure advertised “the elegant and cosy coffee restaurant with open terrace and view of the English Garden”, as well as “the beer parlour in the basement” (which has been home to the P1 disco since the late 1970s) and “the delightful bar with dance floor”, which is “popular for its intimate artistic design”.[38]

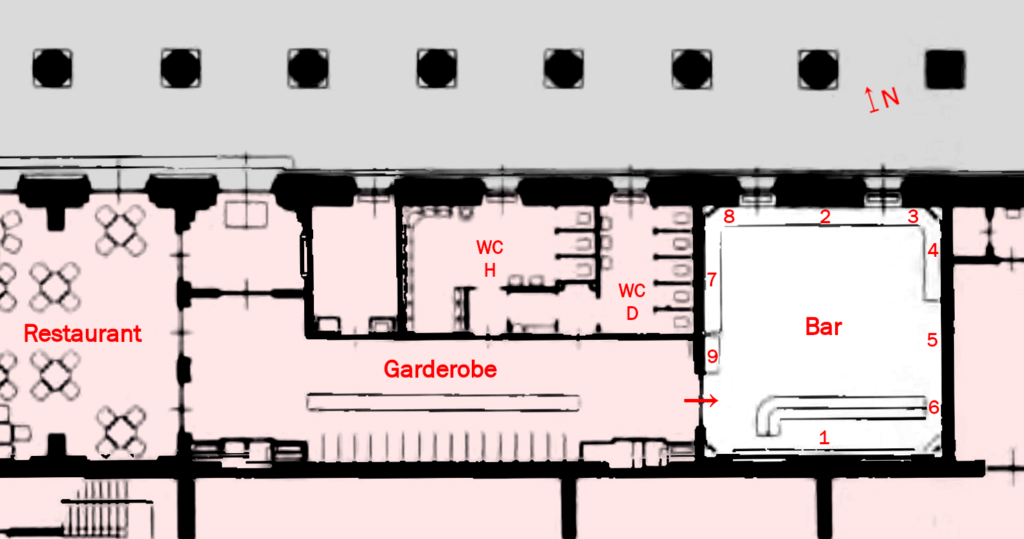

The “Golden Bar” was not prominently located within the building. Coming from the main entrance in Prinzregentenstraße, the path led straight ahead through the vestibule into the large “Hall of Honour”, which Hitler used every year to stage himself as part of the opening speeches for the GDK. Behind it, like the transept of a church, was the restaurant with its generous window front facing the terrace and the English Garden (today the Terrassensaal). In the far right corner of the long hall, the premises of the Goldene Bar begin today. In its original state, however, you first entered the corridor-like cloakroom with the adjoining toilets – also via the north entrance from the terrace. Hidden behind it, the only entrance led to the small, shimmering golden room, the effect of which must have been greatly enhanced by the surprise behind the sober neoclassicism of the museum building and the rows of coats and umbrellas without direct daylight. Even today, entering the Goldene Bar in the evening gives you the feeling that you have found a secret room hiding a treasure. The cube-shaped bar room that opens up in front of you speaks a completely different, more neo-baroque language than the rest of the building in terms of its overall design. This contrast between “monumentality and cosiness”,[39] i.e. between the image presented by the bar and the sober Nazi representative architecture around it, did not escape the notice of contemporaries: “The picture has a delightful lightness and grace. It shows that our time is not only characterised by seriousness and determination, but that it is also capable of celebrating cultivated festivities.”[40] It goes without saying that the purpose of the bar was to celebrate.

There were bistro tables with dark wood chairs in front of surrounding benches with red upholstery. Above the surrounding wood panelling up to the height of the bar, the area was or is divided vertically by ornamental wooden panels. In between are wall panels of varying sizes with the famous paintings on a gold background,[41] divided by narrow mirrors or, opposite the bar, two high windows overlooking the English Garden. The white ceiling above a cornice, which is structured by restrained stucco mouldings around the edges, prevents the room from appearing overly crowded. The geographical theme of the paintings, which will be discussed below, was taken up by a large compass rose, which, as a multi-coloured inlay in the parquet floor, marked the centre of the room and presumably also the dance floor. The photo in the GDK leaflet clearly shows a piano in front of the bar, below the map of England on the east wall. Music and dancing played a major role in German bars of the time. Plain, angular bar stools were joined by coat hooks and a foot bar at the counter. Behind them, a neo-baroque-style shelf towered high, which is still in use today as back bar. Like the ornamental wooden panels between the wall panels, the shelf is now painted a dark green colour. Originally, however, the work was wood-coloured, i.e. brown.[42] The distinctly different design language and (interior) architecture of the bar does not originate from the Troost studio, but is a late work by Munich architect Ernst Haiger (1894-1952).[43]

Wonderful world of wine – the bar’s picture programme

However, the “Golden Bar” was named after the gold ground paintings by Munich artist Karl Heinz Dallinger. He applied small, square pieces of gold leaf to wooden panels, creating a chequered, textured picture surface, like graph paper. The warmth and solemnity of the applied tempera painting makes them reminiscent of the Wilhelmine mosaics in Aachen Cathedral, which in turn are modelled on Byzantine paintings. All the pictures follow a similar structure: a specific region is depicted as a geographical map. In addition to the characteristic outlines, the lettering reveals their location. Also, figures cavort in open spaces, showing the steps of wine and spirits production like in a children’s book.[44] The endeavours to achieve cartographic accuracy in the coastlines and river courses of the maps depicted are impressive.

The only area (1) that can do without being divided into smaller fields is the wall above the bar, which shows German wine-growing regions across the full width of the room. Here it is not the contours of the country but the courses of the famous Moselle, Rhine and Main rivers with their important tributaries. The wine-growing regions of Moselle, Rheingau, Palatinate and Franconia are named, with the coats of arms and names of important places in the region underneath. Castles are marked along the rivers and hills, most of which are labelled. In the centre above the Rhine, to the west of Wiesbaden, lies a bearded figure with an oversized wine glass and a crown of vine tendrils, as if reclining for a feast. It looks like a hybrid of ancient depictions of the wine god Bacchus and the river god Rhenus. In the marginal areas, people can be seen pressing wine, a cellar master checking the wine, a woman harvesting grapes and two women descending a staircase with a basket and jugs.[45] Here, a song of praise is sung to the winegrowers, paying homage to their work and their products.

On the opposite wall, between the two windows (2), there is a depiction of the Champagne province, again showing the course of rivers dividing a series of hills and vineyards: this time the Marne with its tributaries. The twin towers of Reims Cathedral are clearly recognisable. Only at the bottom of the picture does the viewer come across figures in a champagne cellar with the characteristic shaking boards. Instead of a coat of arms, there is the national emblem of France: the letters “RF” for République Française in front of a bundle of rods with an axe. The motif, which had been used in France since the Revolution of 1789, probably reflected the taste of the time: As an ancient emblem of the Roman magistrates, the bundles known as fasces had inspired Italian fascismo inparticular. The Gironde, the elongated basin of the Garonne estuary above Bordeaux, which represents the great wines of southern France, nestles in the narrow wall panel to the right of the windows (3). France is thus represented in the “Golden Bar“with two wall panels.

From there, it’s just a 90-degree turn to the east wall of the bar, where the Portuguese Algarve can be seen in the left-hand image field (4). To the south of this, a black wooden panel with daily recommendations now conceals the southern tip of Spain, including Cádiz and Malaga. Below the cartographic representation, Dallinger had painted a female winegrower carrying a basket of vines on her head and leading a donkey heavily laden with baskets of wine on a lead. Her headscarf and the basket above it have an oriental feel and are possibly an allusion to Moorish traditions. The peasant woman and donkey come down from a hill on which a castle can be seen, perhaps modelled on the Andalusian Castillo de Almodóvar del Río. At the latest with this field, drinks other than classic wine enter the scene: port wine, sherry, Malaga wine and Spanish brandy come to mind for the discerning drinker.

The centre, largest panel of the east wall (5) shows the outline of Ireland and the British main island up to the Highlands above Edinburgh. Above this, the depiction ends abruptly with the ceiling cornice, as if Dallinger had had problems with the format. The fact that the entire south-west of England from Oxford to Cornwall is missing today is due to an emergency exit, as required by modern fire protection concepts. Conversely, however, this is another indication of how consistently the bar was located in the last corner of the house at the time of its creation. Great Britain is recognised as an old naval and trading power by a large sailing ship and a steamship. The nautical motif of the compass rose from the parquet floor is also taken up again. In the bottom left-hand corner of the picture is a depiction of two people working in a distillery producing whiskey or gin.[46]

To the right, in the small field above the end of the counter (6), Hungary is depicted, which is known for its sweet Tokaj wine. Dressed in Puszta costume, a shepherd rider herds Hungarian steppe cattle with their characteristic long horns; in the background, the poles of the typical draw wells rise up.

Looking back to the entrance side in the west, the much larger of the two panels (7) is dedicated to the Italian boot, which is flanked on the left by Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica and on the right by the Yugoslavian Adriatic coast. The dominant wine theme is further illustrated: In the lower left corner of the picture, an Italian winegrower leans against his horse-drawn cart loaded with barrels. On the right is a scene in which two women and a man are enjoying the fruits of their labour. They are sitting at a table under a vine-covered pergola at the foot of a winding mountain village. Surprisingly, this is the only depiction – apart from Bacchus-Rhenus – in which they are not working, but simply carousing.

To the right of the depiction of Italy, the narrow field next to the window on the north wall (8) shows South Tyrol, which had been part of Italy since 1920. The Adige river can be seen running from Merano to Bolzano, which is sung about as a border river in the Deutschlandlied (in the ominous first verse). At the bottom of the picture is a traditional Saltner, who looks like a mixture of a shaman adorned with feathers and a Swiss Guardsman with a halberd. His function as a vineyard guard in late summer was to protect the ripe vines from birds and other berry thieves.

To the left of Italy (9), perhaps the most surprising depiction nestles around the entrance door in a horseshoe shape: the silhouettes of Jamaica, as well as parts of Cuba and Haiti, are exemplary for the Caribbean islands. Traditional outrigger canoes travel between the islands. On the larger one, you can see five people rowing, loading a stack of barrels or bales of tobacco. To the right of the door, a smoking man in a white jacket and large Panama hat stands in front of bales of tobacco, which are apparently being loaded onto the sailing ship behind. On the left, we see a barefoot man under a windswept palm tree, who is beating sugar cane with a machete. This undoubtedly establishes the rum reference in the last panel.

Karl Heinz Dallinger’s figurative depictions of workers producing wine and spirits, whose work is predominantly close to nature and agricultural, fit in well with the National Socialist idealisation of rural life and simple work. But this idyll was never the exclusive preserve of a Nazi world view. The almost bucolic genre pictures could have been seen in Bavarian or generally traditional German inns both before and after the Third Reich. The generally colonialist style with which we are shown the noble savage on his canoe or with his donkey, as well as the underlying cultural stages world view, were neither an invention of 1933 nor did they die out in 1945. The pictorial programme of the “Golden Bar” and not least the medium of wall painting fit in with the times – but nothing about it is compelling or overtly National Socialist.[47] The seat cushions in NSDAP red do nothing to change this.[48]

The problem of interpreting internationality

On the contrary, the conspicuous cosmopolitanism of the pictorial programme raises problems of interpretation: How do the “multiculti” depictions fitinto the year 1937 and into the House of German Art with its patron Adolf Hitler?

“This painting stood for cosmopolitanism, an important factor for the National Socialist landlords, who, for example, presented themselves internationally at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin and the 1937 Paris World’s Fair. This elegantly disguised the racist core of the National Socialist ‘art temple’ that was the ‘Great German Art Exhibitions’.”[49]

This interpretation from the Haus der Kunst website is not fully convincing. The 1936 Olympic Games were an important step towards establishing the young Nazi Germany in the eyes of a sceptical world public. However, the strategy of presenting itself as international and cosmopolitan was abandoned soon after the Olympic Games.[50] At the World Exhibition in Paris in November 1937, the aim was to present itself on the international stage and position itself among the other powers.[51] The German pavilion, designed by Albert Speer, demonstrated Nazi Germany’s exuberant self-confidence and claim to power with its 55 metre high tower topped by a huge golden Reich eagle with a swastika. The “clumsily ostentatious”,[52] almost phallic cuboid towered over the Soviet pavilion opposite and was even more of a visual distraction from the nearby Eiffel Tower.[53]

In contrast, the “Golden Bar” within the hierarchy of the rooms of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst hardly had the status to disguise the ideological core. Hitler had already clearly rejected the internationality of art in his opening speech on the Day of Art in 1937 and declared art to be “a national affair“.[54] If the intention of the bar concept had been to conceal or distract from the big picture, it should not have been a small and almost hidden appendix to the whole complex. “Of course, it was an insignificant detail in the masterplan of National Socialist cultural policy,” commented the Süddeutsche Zeitung in 2010, shortly before the opening of today’s Goldene Bar.[55] Art historian Kia Vahland, on the other hand, judged that the “maps on the walls proclaim a Greater German world view”.[56] This is not convincing either, because the paintings do not predominantly express a claim to German superiority and hegemony (especially as Baden, Württemberg and the Ahr, important German wine-growing regions, are missing).

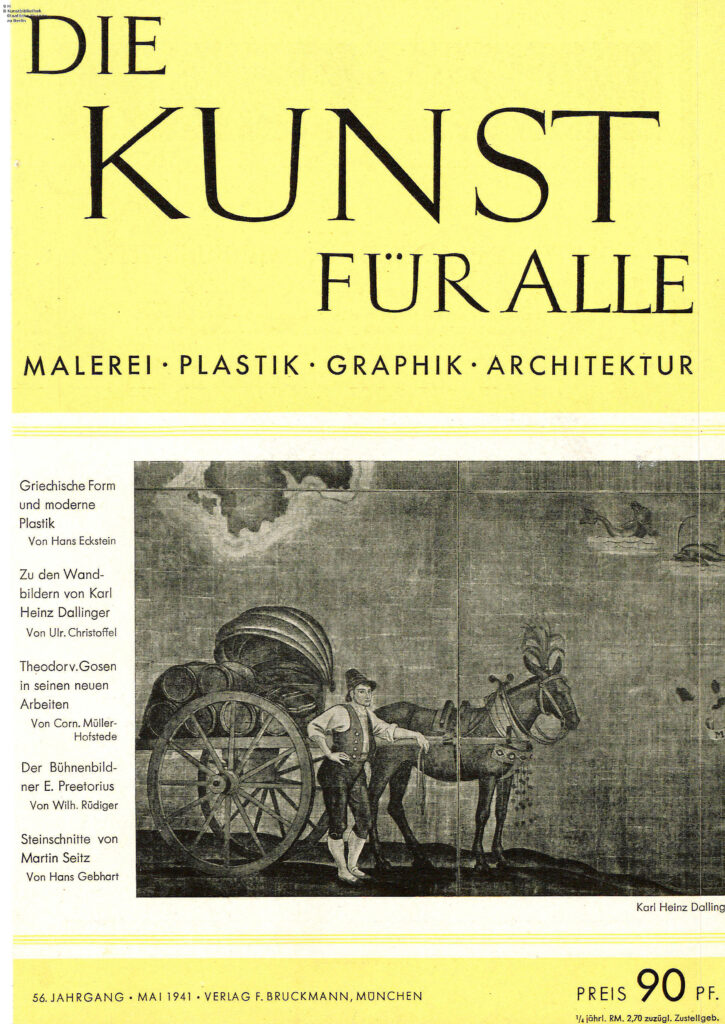

The “Golden Bar” was widely publicised in the Nazi press and in contemporary specialist publications on art and design. It was perhaps mentioned more often than some of the GDK‘s exhibits. In the programmatic Nazi art magazine Die Kunst für Alle, Ulrich Christoffel devoted a multi-page article to Dallinger’s painting of the bar in 1941. However, the Swiss art historian indulged in little more than art philosophical platitudes such as: “The monumental or decorative style of the murals depends on the higher or everyday purpose of a room and on the inner meaning of the representation.”[57] But the expert is silent on precisely this inner meaning. The topic of the cosmopolitan nature of the pictorial programme was not problematised in Nazi journalism – either because contemporaries did not even ask themselves the question, as they saw no problem in the depiction of foreign wine regions from a Nazi perspective – or because they were just as surprised as we are, but preferred not to attract attention with uncomfortable questions.

Ultimately, even the author of these lines cannot resolve the contradiction between the cosmopolitanism displayed and the National Socialist world view. However, it can be assumed that, at least since the rise of the bourgeoisie in the German Empire, there were also Germans who had a weakness for Scotch, real champagne, or good overseas rum. As expensive imported goods, such passions were primarily reserved for the wealthy elite from business and politics, who perhaps did not want to do without these pleasures even with a new party membership. The “Golden Bar” could therefore be seen as an enclosed space with a valve function, within the narrow confines of which indulgence posed no threat to the brown world view and could therefore be tolerated.

Furthermore, the depictions on the walls do not reflect the contemporary state of the art in wine production, but show methods and tools that have existed for centuries, carried out by people in old-timey costumes – not in the fashion of the 1930s. In addition to the geographical dimension, the pictorial programme thus also points to a romanticised past. Against the background of the context in which the bar is embedded, the “strangely contradictory combination of cultural-political-propagandistic modernity and longing for a pre-modern ‘order’ of forms”, which is “typical of the entire Nazi aesthetic”, becomes apparent.[58] This is certainly a lesson in the fact that National Socialism was not the rigid and monolithic ideology that we tend to think it was today. The first mistake is to expect the Nazis’ world view to be coherent in itself – after all, the basic assumption that one’s own “race” is above others is a prime example of idiocy.

Perhaps a look at the painter of the “Golden Bar” Karl Heinz Dallinger and his work will help to give a clearer picture.

Part 2: Karl Heinz Dallinger, the painter of the “Golden Bar” ►

Part 3: The “Golden Bar” during and after the war ►

[Translated from German with the help of deepl.com.]

Annotations

[1] Schwarz 2011, 203 ff.; Brantl 2007, 48.

[2] Die künstlerische Ausgestaltung des KdF-Schiffes “Robert Ley”, in: Dresdner Nachrichten, 12.04.1939, S. 3, https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/newspaper/item/7KDZZWFAG3VQ4EYUBWTIKO74LR4KYDLE?tx_dlf&issuepage=3 (26.01.2024).

[3] Hartewig 2018, 138.

[4] Ullrich 2013, 448; Fest 1979, 40 ff.

[5] Kershaw 2013, 48; Schwarz 2011, 40.

[6] Ullrich 2013, 15 f.; Kershaw 2013, 55 f.; Schwarz 2011, 53 ff., 89 f. passim, Fest 1979, 49-53.

[7] Kershaw 2013, 88 ff.

[8] Schwarz 2011, 131 f.

[9] Schwarz 2011, 94 ff.

[10] Ullrich 2013, 448; Krause 2012, 50; Schwarz 2011, 21 ff., 105-115, 149-154 passim.

[11] Krause 2012, 49 f.; Schwarz 2011, 237-255; Petropoulos 1999 111 ff.; Seckendorff 1995, 142.

[12] Schwarz 2011, 269 f., cf. also ibid. 221-235, 306-310. A total of around 6000 works were hoarded on Hitler’s behalf for various destinations; cf. Krause 2012, 52 f.

[13] Ullrich 2013, 448; Schwarz 2011, 155-178, 182-189.

[14] Schwarz 2011, 20 (translated from german); cf. Kershaw 2013, 74; Fest 1979, 724-731.

[15] Schwarz 2011, 30.

[16] Schwarz 2011, 209 (translated from german); cf. Ullrich 2013, 448

[17] Piper 1989, 132.

[18] Adolf Hitler, opening speech Haus der Deutschen Kunst = Christoffel 1937, 289 (translated from german); cf. Vahland 2016b.

[19] Brantl 2017a, 29 f.; Schwarz 2011, 209f.; Piper 1989, 136.

[20] Ullrich 2013, 448; Schwarz 2011, 205 ff.

[21] Andreas Heusler, Hauptstadt der Bewegung, München, Verleihung des Titels “Hauptstadt der Bewegung”, in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns, 23 January 2018, https://www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de/Lexikon/Hauptstadt_der_Bewegung,_M%C3%BCnchen (23 March 2024).

[22] Piper 1989, 138 f.

[23] Adolf Hitler, opening speech Haus der Deutschen Kunst = Christoffel 1937, 289 (translated from german).

[24] Ullrich 2013, 278; Krause 2012, 27 f.; Arndt 1995, 148.

[25] Brantl 2017a, 25 f.; Vahland 2016b; Krause 2012, 31 f.; Brantl 2007, 51; Seckendorff 1995, 148.

[26] Schwarz 2011, 135; Seckendorff 1995, 119.

[27] Strich im Tempel, in: Der Spiegel 17/1965, https://www.spiegel.de/politik/strich-im-tempel-a-561f0df3-0002-0001-0000-000046272325 (16.01.2024).

[28] Gerdy Troost, Das Bauen im Neuen Reich, 5th ed., Bayreuth: Gauverlag 1942, 8 (translated from german); cf. Schwarz 2011, 203.

[29] Brantl 2017b, 181.

[30] In addition, the author is a fan of the early work of the band Extrabreit, whose second album “Welch Ein Land ! – Was Für Männer:” with the title “Der Führer schenkt den Klonen eine Stadt …” (The Führer gives the clones a city) (Reflektor Z 1981).

[31] Piper 1989, 136.

[32] Schwarz 2011, 209; Petropoulos 1999, 79 ff.

[33] Brantl 2017a, 31 f.

[34] Brantl 2017b, 181 ff.

[35] Cf. Hartewig 2018, 7 f. For the journal of the same name, see Schwarz 2011, 43-46.

[36] Brantl 2017b, 180.

[37] Brantl 2017b, 180 (translated from german); cf. Hartewig 2018, 7, 200.

[38] Die goldene Bar, Geschichte, 2017, https://www.goldenebar.de/geschichte/ (27.02.2024) (translated from german).

[39] Seckendorff 1995 (translated from german).

[40] Rococo or new style? How should the new ceremonial and meeting hall in Bonn’s old town hall be designed?, in: Mittelrheinische Landes-Zeitung, No. 286, 8 December 1938, 3, https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/newspaper/item/4GNE2WJL4VOGD5373BKJTIUBAMUD5USB?issuepage=3 (27 February 2024) (translated from german).

[41] The Golden Bar, History, 2017, https://www.goldenebar.de/geschichte/ (27/02/2024).

[42] Rokoko oder neuer Stil? Wie soll der neue Fest- und Sitzungsaal im alten Bonner Rathaus gestaltet werden?, in: Mittelrheinische Landes-Zeitung, Nr. 286, 08.12.1938, 3, https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/newspaper/item/4GNE2WJL4VOGD5373BKJTIUBAMUD5USB?issuepage=3 (27.02.2024) (translated from german).

[43] Brantl 2007, 55.

[44] Hartewig 2018, 137.

[45] The staircase is architecturally framed; Christoffel 1941, 175, subtitled: “An der Weinbergstiege.”

[46] Hartewig 2018, 137.

[47] Hartewig 2018, 120 At the very least, the paintings could presumably be dated by the composition of the towns and their coats of arms on the picture of Germany. For example, the coat of arms of Nieder-Ingelheim with eagle and red castle wall can be seen for Ingelheim before it was incorporated into Ingelheim in 1939. However, the political statements that should be contained therein elude the viewer who does not intensively analyse the background. Cf. Görl 2010.

[48] Brantl 2007, 53.

[49] Haus der Kunst, Ihr Besuch, Goldene Bar, https://www.hausderkunst.de/ihr-besuch/goldene-bar (10 March 2024) (translated from german); see also Brantl 2007, 55 f.: “However, the suggestion of an international flair was an essential element of Nazi propaganda and was intended to strengthen the national self-confidence of the “Volksgenossen” and to give foreign countries an impression of the cosmopolitan nature of German visions” (translated from german).

[50] Schwarz 2011, 218.

[51] Cf. Brantl 2017a, 26: “In addition, National Socialist Germany wanted to raise its profile as a cultural nation on an international level” (translated from german).

[52] Arndt 1995, 154 (translated from german).

[53] A large architectural model of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst was exhibited on the “podium of honour” in the German pavilion; see Haus der Kunst, Exhibitions – 10.6.12 – 13.1.13: Geschichten im Konflikt: Das Haus der Kunst und der ideologische Gebrauch von Kunst 1937-1955, https://www.hausderkunst.de/eintauchen/geschichten-im-konflikt-das-haus-der-kunst-und-der-ideologische-gebrauch-von-kunst-1937-1955 (10.03.2024). On the significance of this architectural model and Germany’s participation in the Paris World Exhibition, see Brantl 2017a, 26 ff.; Bartetzko 1985, 52.

[54] Brantl 2017a, 29 (translated from german). – Cf. Adolf Hitler, opening speech Haus der Deutschen Kunst = Christoffel 1937, 276: “Beginning with assertions of a general nature, such as that art is international, through to analyses of artistic creation using certain basically meaningless expressions, there was a continuous attempt to confuse common sense and instinct. By presenting art on the one hand only as an international communal experience and thus killing any understanding of its connection to the people, it was linked all the more to time, which means that there was no longer any art of peoples or, better, of races, but only an art of the times…” (translated from german).

[55] Görl 2010 (translated from german).

[56] Vahland 2016a (translated from german).

[57] Christoffel 1941, 171 (translated from german).

[58] See Bartetzko 1985, 52: “As architectures that appear as modern in their archetypal purism as their immediate predecessors from the last years of the Weimar Republic, but at the same time stand before our eyes as the return of ancient traditions, they seal the absurd assertion of the Third Reich as a simultaneously restorative and radically renewing state.” (translated from german)See also Hartewig 2018, 9; Brantl 2007, 56, with note 121.

Abbreviated references

Click here.