[German version | List of historical bars]

- Part 1: The Führer gives the people of Munich a bar

- Hitler and art

- The House of German Art

- The “Golden Bar” 1937

- Wonderful world of wine – the bar’s picture programme

- The problem of interpreting internationality

- Part 2: Karl Heinz Dallinger, the painter of the “Golden Bar”

- For a drink in the “Führerbau”

- Decorator of power

- A cocktail shaker for Siemens: Dallinger after 1945

- Part 3: The “Golden Bar” during and after the war (05.04.2024)

- Abbreviated references

Part 3: The “Golden Bar” during and after the war

[Estimated reading duration: 21 minutes]

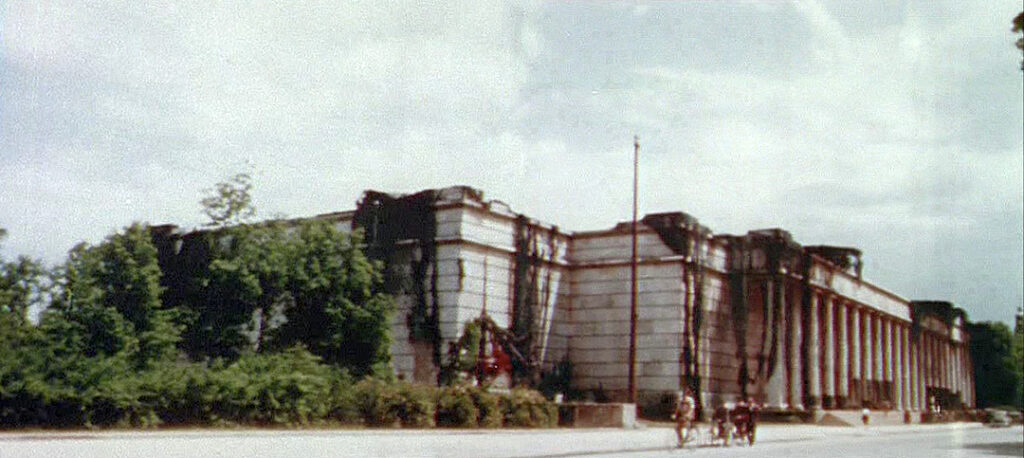

The Haus der Deutschen Kunst survived the Second World War largely unscathed, although the bombings reached Munich in March 1943 barely a month after Joseph Goebbels had declared “Total War” in the Berlin Sports Palace.[127] By this time, Hitler’s prestige project had already visually merged with the English Garden through camouflage nets and artificial treetops on the roof,[128] so that the Große Deutschen Kunstausstellungen (GDK – Great German Art Exhibitions) werestill held in the same summer and in 1944. The enormous importance of the institution can also be seen from the fact that the “Führer” ordered the preparation of the GDK for the summer in February 1945, three months before his suicide and before Germany’s overdue capitulation.[129] The exhibition catalogues indicate that catering was also continued. Sabine Brantl assumes that operations continued “without restrictions”.[130]

Cocktails in Hitler’s temple of art?

But what was drunk in the “Golden Bar”? Can we read the pictorial programme like a bar menu? While this is often assumed today,[131] the tenants at the time did not necessarily follow the programme. Moreover, during the course of the war from 1939 onwards, many a bottle must have been difficult to obtain. On the other hand, it was to be expected that the sight of the illustrations would arouse desire among guests. Against this background, the restriction to Bavarian lager and pots of coffee is unlikely, despite the mass audience.

From the advertisements in the exhibition catalogues, we know that Löwenbräu had secured the beer monopoly in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst for itself.[132] In the catalogue for the opening year, the Palatinate winery Schwarzwälder from Diedesfeld near Neustadt also advertised that its wines were available in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst.[133] The Anton Riemerschmid brandy distillery and liqueur factory, which today is primarily known for its bar syrups, placed an advert,[134] without it being possible to say whether the liqueurs were available in the “Golden Bar”. The same applies to Dujardin, which from 1810 was the first company to distil German cognac with wines from the Charente. It was advertised in the GDK catalogue in 1943,[135] before the production facilities in Uerdingen on the Rhine were destroyed in an air raid that same summer.[136]

Fig. left: Advertisement Riemerschmid in: Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung 1944. Offizieller Ausstellungskatalog, Munich: F. Bruckmann 1944, 38.

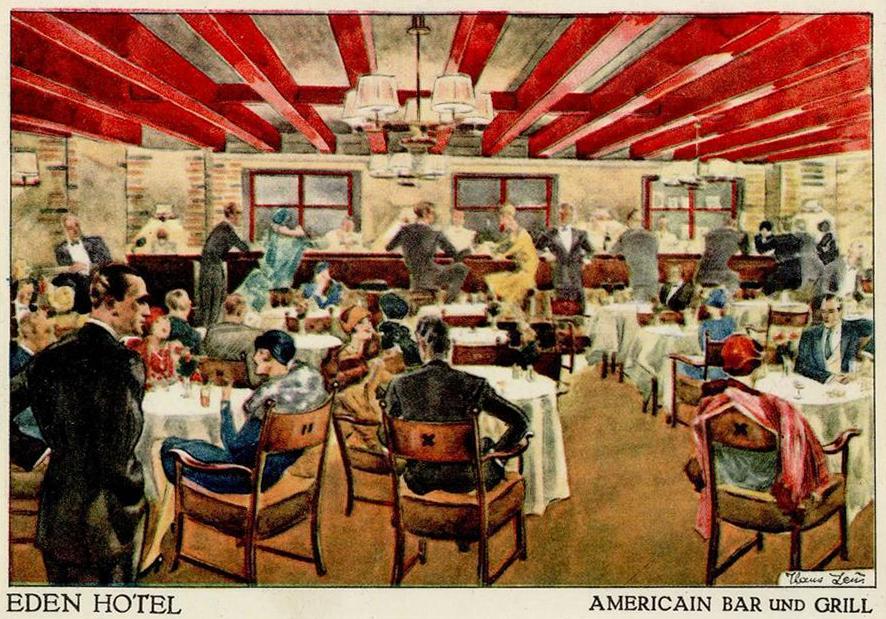

Cocktails had been established in Germany since the emergence of American bars at the end of the 19th century, often as part of a hotel business. However, the initially incomprehensible term “bar” took on a life of its own in German, acquired a somewhat disreputable connotation and became associated above all with dancing and music. In Germany, cocktails were not an essential feature of a bar, especially as German drinkers liked to sip liqueurs and spirits alongside beer, wine and sparkling wine, without mixing them together in any way. The American origin of the cocktail was anchored in the collective consciousness of the Germans. But this did not prevent the noble, cool mixed drinks from existing even after 1933. On the one hand, everything un-German was ostracised, disrespectful comments were made about foreign mixed drinks and Italian comrades were called upon to stick to their vermouth so as not to bleed the local winegrowers dry.[137] On the other hand, we only hear about the Nazis’ actions against bars in connection with Jewish operators or artists who were caught up in the deadly machinery of the Holocaust. Running a bar in itself was apparently not un-German enough to become a target.

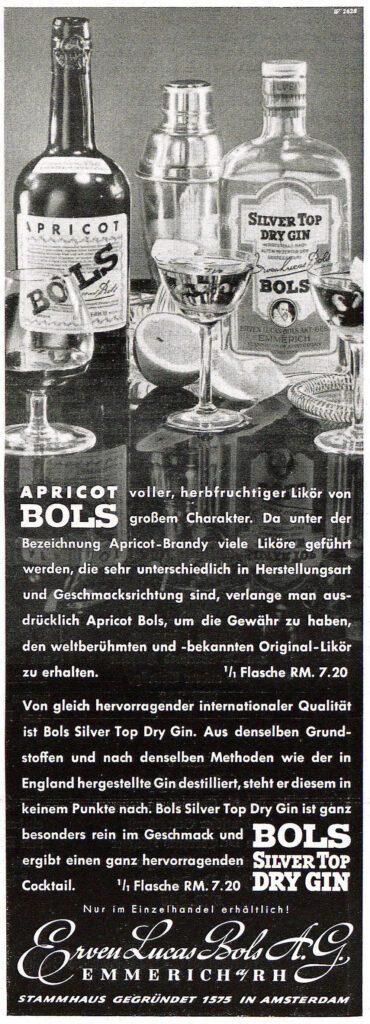

The cocktail phenomenon does not appear to have been a problem that the Nazis focussed on. A few cocktail books from Germany between 1933 and 1945 are known, the most famous of which today is probably “Das kleine Mixbüchlein”, self-published by Fritz Waninger from Munich in 1940.[138] The Bols company, which had been an integral part of the world of liqueurs and spirits since the late 16th century, regularly placed adverts in the magazine Die Kunst für Alle. In December 1940, they advertised in a highly modern way with a photo of their own products, which also showed a classic Cobbler shaker. It featured the technically elaborate inscription: “Bols Silver Top Dry Gin has a particularly pure flavour and makes an excellent cocktail.”[139]

Hitler himself was outspoken abstinent when it came to alcohol – this is widely known.[140] Even as a young man in Vienna, he was already working on the idea of an alcohol-free “people’s drink”.[141] Nevertheless, the “Führer” apparently let his followers have their fun. In the end, Rudolf Hess had to give up his corner office in the “Führerbau” in favour of the bar – which also astonished his contemporaries: “Although the Führer himself was against the consumption of alcohol and tobacco, he provided a magnificent smoking room and bar for his guests.”[142] It was precisely here in Munich that the “movement” had its beginnings in beer bars. [143]

That Hitler had a weakness for cocktails, on the other hand, can probably be ruled out. Nevertheless, bar utensils from his immediate neighbourhood have been preserved. A cobbler shaker with a handle and engraved swastika flag has survived from the officers’ mess of the “Grille”, a light warship of the Aviso type, which served as Hitler’s personal yacht.[144] The American collector Stephen Visakay owns a silver set with a Hawthorne strainer, a lemon squeezer with the initials “AH” and a curved tin-in-tin shaker with a national emblem. The ensemble was apparently taken by an American officer in April 1945 during the capture of Hitler’s residences on Obersalzberg.[145] Provided these objects are not all forgeries, they prove that cocktails were tolerated in principle even in Nazi leadership circles.

Americans, carnivalists and critical deconstruction

When American troops marched into Munich on 30 April 1945, the Haus der Deutschen Kunst was confiscated. The American military government could not leave a large, undestroyed building with a functioning infrastructure unused. An Officers’ Club was set up for leisure activities. The G.I.s painted markings for a basketball court on the floor of the former “Hall of Honour”.[146] In addition to a canteen and a dance hall, there was a bar that offered the officers affordable drinks in the style of the distant homeland: “A champagne ‘Pick me up’ cost 40 cents in the Officers’ Club, a cocktail like ‘Pink Lady’ or ‘Edelweiss’ 50 cents.”[147] It is hard to imagine that the “Golden Bar” was not used for this. Whether shakers, strainers and jiggers were already available remains a mystery for the moment. By now, at the latest, there were proven to be cocktails in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst. Cocktail enthusiasts can imagine what “Pick me ups” and “Pink Ladies” were, but what an “Edelweiss” was must unfortunately remain uncertain. The name of the famous mountain flower was a nearby choice for Americans in Munich near the Alps, especially as there were also military connections: German mountain troops of the Waffen-SS had worn it as an emblem and the Luftwaffe’s Fighter Wing 51 was known as the “Edelweiss Wing”. The Americans were perhaps aware of “Operation Edelweiss”, which aimed to capture Hitler in the final phase of the war.[148]

In January 1946, less than a year after the end of the war, exhibition operations were resumed and the building reopened under a new name as the Haus der Kunst (HdK – House of Art). The Americans’ aim was to use culture to teach Germans about democracy and tolerance.[149] In 1948, the building was handed over to the Bavarian state.[150] In the years that followed, the HdK “developed into a central location for German and international modernism […] whose destruction it was originally intended to symbolise.”[151] From 1949, the HdK hosted carnival parties organised by the Museumsverein, which were not reserved for American soldiers and made a lasting impression on the people of Munich: “For 25 years, the building was a carnival stronghold. My grandparents told me about it,” reports Sabine Brantl.[152] The “Goldene Bar” was described by contemporary witnesses as “the best jazz club in the world”.[153] However, the bar did not shimmer golden for much longer: In the 1950s, plywood panels were screwed over Dallinger’s pictures, which were decorated by the painter Gyorgy Stefula (1913-1999) with idyllic scenes from Nymphenburg Park in the west of Munich – “and the disreputable past was magicked away”.[154]

The post-war history of the HdK was and is characterised by a struggle to find the right way to deal with the site’s Nazi past.[155] This applies both to the art on display and to the building itself. The controversially discussed approaches ranged from actual remodelling measures with the aim of hide the monumental character of the building,[156] to complete demolition plans (to which, however, only the large flight of steps in front of the main entrance fell victim in 1971). [157]

A clear paradigm shift took place in 2003 when the then director of the Haus der Kunst Foundation, Chris Dercon, took office. In order to “free Munich from its reputation as the capital of repression”,[158] he focussed on a transparent examination of the burdensome legacy under the slogan “kritischer Rückbau” (critical deconstruction).[159] On the one hand, historical documentation and reappraisal was promoted, including through the opening and cataloguing of the archive, which is still managed by Sabine Brantl today. On the other hand, a comprehensive reconstruction to the original state of the Nazi era was carried out. The break with what the site stood for was to be achieved primarily through the exhibited works of “often unruly international contemporary art“.[160] Of course, this approach did not go unchallenged:

“Now there should be no more grass growing over history, now everything should be out in the open. Is this transparency, a victory for the democratic understanding of history? Or, on the contrary, a capitulation to the force of gigantomaniacal world designs, in which it is also quite easy to dine, celebrate and enjoy art?”[161]

Art critic Kia Vahland comes to the conclusion that this is “not democratisation, but pure unimaginativeness.”[162] The zero solution is the simplest solution for many problems, but is quickly suspected of being lazy. Statements such as “walls are not to blame“[163] or “it sits so well here, nobody has ever complained about it”,[164] do not help to counter this suspicion.

The HdK is certainly special in terms of its original function and significance in the Third Reich. Nevertheless, countless products of Nazi art and architecture, sometimes unrecognised, but mostly unnamed, are simply there and are an unchallenged part of the familiar living environment in Germany – including one or two from the hand of Karl Heinz Dallinger. Just as it was difficult to conjure up artists, architects and air force commanders without a brown past after 1945, this applied even more to works of art and buildings that had survived the war unscathed. Historian Katrin Hartewig also sees irrational motives at work in a fundamental cancel culturetowards the art of the Third Reich: “Many contemporaries still fear a kind of ideological contamination that could emanate from this art. To put it bluntly, anyone who looks at ‘Nazi art’ would immediately become a Nazi.”[165]

Through such fears, the brown propaganda is granted exactly the power it had claimed – only in reverse. The exemplary, very different voices demonstrate that even almost 80 years after the end of the “Thousand-Year Reich”, the HdK is forcing a critical examination of the darkest chapter in German history. Dealing with the past is not a state that is achieved, but a continuous process that must always be orientated towards the challenges of its own time. Current cultural policy demands from the right-wing fringe of the party range are sometimes reminiscent of the concept of “degenerate art“[166] and make the exhibitions, which can be visited today with a cocktail in the Goldene Bar, a thorn in the brown flesh:

“Since its opening in July 1937, the Haus der Kunst had developed from the most important venue for National Socialist art representation into a central location for German and international modernism, whose destruction it was originally intended to symbolise.”[167]

The Goldene Bar today and the legacy from back then

After almost half a century under plywood, the bar’s golden murals were uncovered during renovation work in 2003.[168] The bar was used as a café and occasionally included in exhibitions. As part of his 2006 exhibition “ON/OFF”, industrial designer Konstantin Grcic contrasted the aesthetics of the bar with white beer tables and benches that were nested inside each other in such a way that you had to cross a bridge to enter the centre of the room.[169] When the bar was thoroughly renovated in 2010, the “critical deconstruction” reached its limits, as the original condition was not clear in some details. The Süddeutsche newspaper called on contemporary witnesses to contact the HdK with information.[170] (As shown above, the bottom layer of green paint on the old wooden elements was not the original condition…)

Klaus St. Rainer, who was working as a bartender at Schumann’s at the time,and his partner Leonie von Carnap won a call for proposals against 48 competitors and were able to open the bar, which is now officially called Die Goldene Bar, on 14 October of the same year. In addition to a daytime café, there is an extended evening opening that invites you to savour classic cocktails with a modern twist that are second to none. “Just as we creatively and responsibly interpret the historic rooms, which were ‘rediscovered’ in 2003, with new ideas,” explains Rainer, “I also deal with the drinks.”[171] Despite the purism of the “critical deconstruction”, the bar bears its own signature with a mix of mid-century furniture and a 1920s chandelier from the Hotel Savoy in Zurich as well as crude graffiti scribbles and a large illuminated picture by Munich painter Florian Süssmayr.[172]

In contrast, Karl Heinz Dallinger’s murals in the hip surroundings are completely out of time. Some guests may not even realise how old they actually are. The fact that they fulfil more or less the same function today as they did in the Third Reich, namely to beautify people’s drinking, only causes a disturbing feeling if you actively engage with their context and history, as happened here. However, if one accepts the idea of “critical deconstruction”, the bar also works.

Fig. left: Okwui Enwezor in the Goldene Bar, Director of the Stiftung Haus der Kunst gGmbH 2011-2018, deceased 2019, with the kind permission of the photographer Maximilian Geuter.

The worst case scenario would probably be that the HdK would become a pilgrimage centre for neo-Nazis as an oversized “Führer” relic. When you read that the Bavarian AfD parliamentary group leader thought it was a good idea to spend an evening in the Goldene Bar, the author at least feels uneasy. But when you go on to read that the same person was expelled from the bar when she was recognised,[173] there is optimism that the vision of former HdK director Okwui Enwezor may have materialised: He was dreaming, reports Süddeutsche,

“of a cosmopolitan meeting place, a cultural centre in which not only contemporary art comes into its own, but also discussion rounds, stage events and readings. A place where you can go without a reason to eat something, read the newspaper or meet people. The more life takes place here, the more bearable the burden of history becomes in the eyes of the native Nigerian.”[174]

The author is looking forward to a cocktail in the Goldene Bar on his next visit to Munich.

◄ Part 1: The Führer gives the people of Munich a bar

◄ Part 2: Karl Heinz Dallinger, the painter of the “Golden Bar”

[Translated from German with the help of deepl.com.]

Annotations

[127] Schwarz 2011, 107.

[128] Haus der Kunst, Über uns, History, https://www.hausderkunst.de/ueber-uns/geschichte/chronik (10.03.2024).

[129] Express letter from the Reich Ministry for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda dated 5 February 1945 to the director of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst, reprinted in: Brantl 2017b, 269; cf. ibid. 179.

[130] Brantl 2017b , 179 (translated from german).

[131] Cf. Hartewig 2018, 137: “His wall-filling frescoes [sic] on a gold-coloured background showed the countries and regions of origin of all the spirits, wines and smoked products on the menu” (translated from german). See also MIXOLOGY BAR TV – Bartender 360° – Klaus St. Rainer, in: YouTube, 16.09.2015, 1’53, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sr5v3KyICY4&t=1m53s (11.03.2024): “What’s interesting is that all the scenery around here, which all has to do with drinking, was intended at the time to be a projected drinks menu. Everything on the walls used to be available to order in this bar” (translated from german).

[132] See, for example, Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung 1937, Offizieller Ausstellungskatalog, Munich: Knorr & Hirth 1937, 49, https://archive.org/details/grosse-deutsche-kunstausstellung-1937_202311 (11/03/2024). On the situation of large breweries in the Third Reich, see Ambros Waibel, “Lauter betrunkene Volksgenossen”. Historikerin über Nazis und Bier (interview with Dorothea Schmidt), in: taz, 20. 1. 2020, https://taz.de/Historikerin-ueber-Nazis-und-Bier/!5654865/ (01.03.2024).

[133] Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung 1937. Offizieller Ausstellungskatalog, Munich: Knorr & Hirth 1937, 47, https://archive.org/details/grosse-deutsche-kunstausstellung-1937_202311 (11/03/2024).

[134] Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung 1944. Offizieller Ausstellungskatalog, Munich: F. Bruckmann 1944, 38, https://archive.org/details/grosse-deutsche-kunstausstellung-1944_202311 (13/03/2024).

[135] Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung 1944. Offizieller Ausstellungskatalog, Munich: F. Bruckmann 1943, 51, https://archive.org/details/grosse-deutsche-kunstausstellung-1943_202311 (13/03/2024).

[136] Dujardin (Unternehmen), in: Wikipedia. Die freie Enzyklopädie, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dujardin_(Unternehmen)#Geschichte (27 February 2024); see also Ehmer & Hindermann 2022, 19 f.

[137] R. S., Contra Cocktail. Italiener trinken Wermut, in: Die neue Woche. Sonntagsbeilage zum Neuen Tag, Köln, 20.06.1937, 7, https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/newspaper/item/IWG6MPOM4WJ3UY3TMR7KI3FVRQFNVFNR (04.03.2024).

[138] Fritz Waninger, Das kleine Mixbüchlein. 50 Standardgetränke nebst einer Anleitung zum Mixen, Munich: Selbstverlag 1940; cf. Martin Stein, Wie ein kleines Barbuch aus München die American Bar unter den Nazis weiterleben ließ, in: Mixology. Magazin für Barkultur, 15.10.2019, https://mixology.eu/american-bar-nazis-franz-waninger-muenchen/ [sic] (04.03.2024).

[139] Die Kunst für alle. Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 56. Jahrgang, Heft 3, Dezember 1940, München: F. Bruckmann, 21, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/kfa1940_1941 (04.03.2024) (translated from german).

[140] Kershaw 2013, 79, 82; Ullrich 2013, 453.

[141] Kershaw 2013, 74 (translated from german); Fest 1979, 52.

[142] Adolf Dresler, Das Braune Haus und die Verwaltungsgebäude der Reichsleitung der NSDAP, Munich ³1939, 36, cited in Seckendorff 1995, 138 (translated from german).

[143] Ambros Waibel, „Lauter betrunkene Volksgenossen“. Historikerin über Nazis und Bier (Interview mit Dorothea Schmidt), in: taz, 20. 1. 2020, https://taz.de/Historikerin-ueber-Nazis-und-Bier/!5654865/ (01.03.2024); Kershaw 2013, 173 ff.

[144] The Saleroom, lot 6862, Auktionshaus Hermann Historica, Munich 12.12.2014, https://www.the-saleroom.com/de-de/auction-catalogues/hermann-historica-ohg/catalogue-id-srher10000/lot-ed5378ae-6b9f-4c70-934b-a40100e11531 (30.03.2024).

[145] Aimee Lee Ball, Elements of Style. Drink Time for Hitler, in: GQ 12/1994, 66, https://www.aimeeleeball.com/Site/GQ_files/Cocktail%20Shakers.pdf (20 March 2024).

[146] Strich im Tempel, in: Der Spiegel 17/1965, https://www.spiegel.de/politik/strich-im-tempel-a-561f0df3-0002-0001-0000-000046272325 (22/02/2024).

[147] Hitlers Schatzbücher im Keller, in: Focus Online, 12.11.2013, https://www.focus.de/kultur/kunst/hitlers-schatzbuecher-im-keller-zeitgeschichte_id_2294953.html (22.02.2024). On drinks as a “bridge to the homeland”, see Rudeck 2023, 206 ff.

[148] Leontopodium nivale, Symbolic uses, World Wars, in: Wikipedia. The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leontopodium_nivale#World_Wars (20/03/2024).

[149] Brantl 2017a, 34 f.; cf. Enwezor 2017, 16.

[150] Brantl 2020, Der Ausstellungsbetrieb nach 1945.

[151] Brantl 2017a, 41 (translated from german).

[152] Hitlers Schatzbücher im Keller, in: Focus Online, 12.11.2013, https://www.focus.de/kultur/kunst/hitlers-schatzbuecher-im-keller-zeitgeschichte_id_2294953.html (22.02.2024) (translated from german).

[153] Monumentaler Arbeitsplatz – gepe reinigt das „Haus der Kunst“ in München, in: gepe’chen 3, August, 2020, 7, https://www.gepe-peterhoff.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/gepechen0320.pdf (13.03.2024) (translated from german).

[154] Görl 2010 (translated from german).

[155] Enwezor 2017, 16 f.; Vahland 2016; Görl 2010.

[156] Die goldene Bar, Geschichte, 2017, https://www.goldenebar.de/geschichte/ (27/02/2024).

[157] Strich im Tempel, in: Der Spiegel 17/1965, https://www.spiegel.de/politik/strich-im-tempel-a-561f0df3-0002-0001-0000-000046272325 (22/02/2024).

[158] Geiger 2005 (translated from german).

[159] Görl 2010.

[160] Vahland 2016a (translated from german).

[161] Vahland 2016a (translated from german).

[162] Vahland 2016a (translated from german).

[163] Görl 2010 quotes Christoph Vitali, the former director of the HdK (translated from german).

[164] Vahland 2016a quotes Okwui Enwezor, also a former director (translated from german).

[165] Hartewig 2018, 13 (translated from german).

[166] Cf. Deutscher Bundestag, Parlamentsnachrichten, AfD-Fraktion will Kulturpolitik grundsätzlich neu ausrichten, Kultur und Medien — Antrag — hib 40/2023, 19 January 2023, https://www.bundestag.de/presse/hib/kurzmeldungen-929882 (7 March 2024).

[167] Brantl 2017a, 41 (translated from german).

[168] Monumentaler Arbeitsplatz – gepe reinigt das „Haus der Kunst“ in München, in: gepe’chen 3, August, 2020, 7, https://www.gepe-peterhoff.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/gepechen0320.pdf (13.03.2024).

[169] Die goldene Bar, Geschichte, 2017, https://www.goldenebar.de/geschichte/ (27.02.2024); Walter Kittel, On/Off, in: Deutschlandfunk, 19.03.2006, https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/on-off-100.html (13.03.2024).

[170] Görl 2010.

[171] Rainer 2014, 6.

[172] Die goldene Bar, Geschichte, 2017, https://www.goldenebar.de/geschichte/ (27/02/2024).

[173] Johannes Heininger, Klaus-Maria Mehr & Sven Rieber, AfD-Politikerin fliegt aus Münchner Bar – darum war das NO Diskriminierung, in: TZ München, 22.11.2018, https://www.tz.de/muenchen/stadt/altstadt-lehel-ort43327/afd-politikerin-ebner-steiner-fliegt-aus-bar-in-muenchen-darum-war-keine-diskriminierung-zr-10559829.html (23.02.2024); Philipp Gaux, Da ist die Tür: Die AfD muss leider draußen bleiben! A commentary on domiciliary rights, in: Mixology. Magazin für Barkultur, 01.12.2018, https://mixology.eu/hausrecht-bar-ebner-steiner-goldene-bar/ (07.03.2024).

[174] Vahland 2016a (translated from german).

Abbreviated references

Click here.