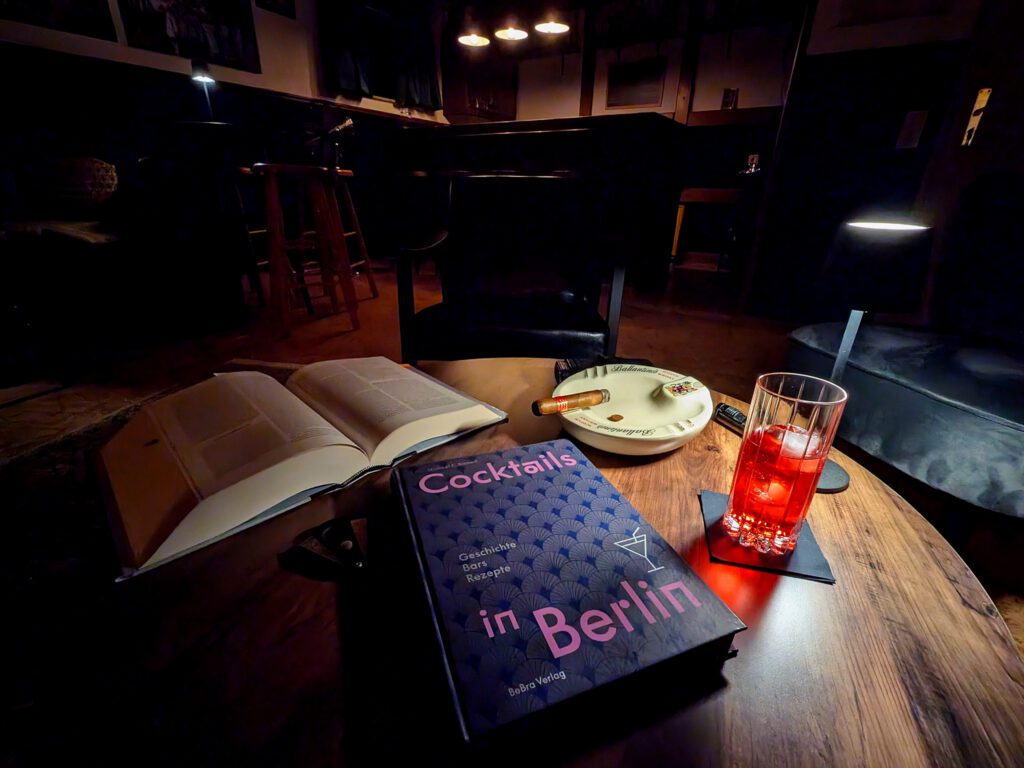

Review: Michael C. Bienert, Cocktails in Berlin. Geschichte – Bars – Rezepte (Cocktails in Berlin. History – Bars – Recipes), Berlin: BeBra publishers 2024, hardcover, 240 pages, 150 illustrations and photographs, ISBN 978-3-8148-0305-0, 28,- €

The historian Michael C. Bienert has written the first coherent history of cocktail culture in Germany. Admittedly, the title of the book ‘Cocktails in Berlin’ already reveals that the account is geographically limited. In addition, there are other aspects that limit the validity of the first sentence and which we still have to deal with. But on the one hand, this book is a must-read for anyone interested in the historical cocktail culture in Berlin and Germany – indeed, in Europe. Secondly, Bienert offers more than ‘just’ history. Unfortunately, the text is currently only available in German.

Michael C. Bienert, Dr phil., born 1978, is director of the Ernst Reuter Archive Foundation. He teaches Modern History at the University of Rostock and at the TU Berlin.

As the subtitle suggests, the book is divided into three very different parts, which I would like to present below: History, Bars and Recipes.

History

The first part of the book offers the history of cocktail and bar culture in Berlin in small, handy chapters. Although ‘Cocktails in Berlin’ is a scholarly but ultimately popular account in the best sense of the word, it is incredibly enjoyable and entertaining to read. Only nerds like me will miss the footnotes and detailed evidence. To compensate for this, there is no shortage of historical illustrations.

Bienert provides a summary of the origins and earliest development of cocktail culture in the USA in two short overview chapters, whereby it should be noted that this part of the narrative, with which almost every cocktail book begins, has rarely been so well done and succinct. It quickly becomes clear that he has thoroughly analysed the works in his bibliography.

Suddenly, we find ourselves in the booming Berlin of the 19th century, which awakens to its bustling life as a young metropolis in just a few pages. Here Bienert picks up the leitmotif that he maintains throughout the entire historical section of the book: places, people and drinks are always embedded in the context of historical development. The ease and aplomb with which Bienert guides us through the turbulent history of Berlin and Germany up to the end of the Second World War is impressive. Even history buffs need not fear being left behind or feeling transported back to the classroom.

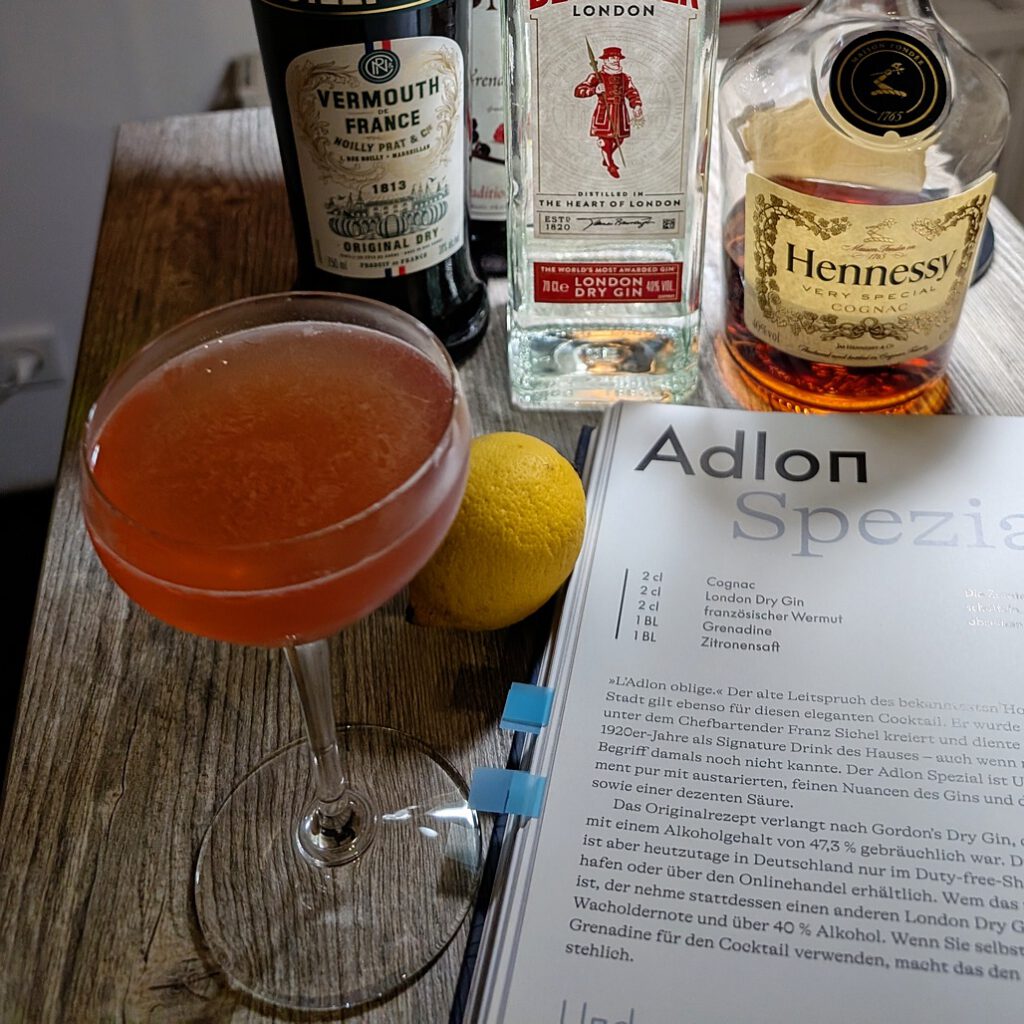

We learn about Berlin’s first American bar, which G. Arnoldi probably opened on Unter den Linden in 1870. Bienert seems to be certain that the bar actually existed (in contrast to my remarks). Soon afterwards, at the end of the 19th century, the American Bar established itself as a permanent fixture in Berlin’s gastronomic landscape, especially (but not only) in connection with the large hotels such as the Adlon or the Central Hotel. An international clientele brought the thirst and the necessary cash with them.

Cocktails have always been an expensive pleasure, reserved for a correspondingly well-heeled clientele. Against this backdrop, ‘bodegas’ emerged that offered cocktails at somewhat more moderate prices alongside wines from Spain and Portugal. The first conurbation of bars emerged in the Friedrichstraße area in particular, and from around 1900 onwards, another was established around Nollendorfplatz in Motzstraße. Based on the documented licences for serving liquor, Bienert estimates that there were a three-digit number of bars in Berlin at this time.

At the same time, bars were already starting to evolve away from the classic American bar model and offered live music and dancing. They were also regarded as a hotspot for all kinds of people looking for a mate. (To this day, the word ‘bar’ has a disreputable connotation, especially among older people). Some of the bars offered safe havens for people from what is now known as the LGBTQ community. Regardless of this, the night-time revelry sometimes provoked protest.

‘Some of the bars were not only known for their gin rickey and Ohio cocktails, but also enjoyed a reputation as places to go for a fleeting adventure – if you had the necessary change.’

Under the heading ‘Printed matter about drinks’, Bienert offers a nice overview of the most important German-language publications on cocktails in the period under review. These include Harry Johnson’s book, which was published in Berlin in 1900 and was therefore easily accessible to the German public. (Johnson’s Berlin period is also honoured in a separate chapter.) Of course, Blüher’s ‘Meisterwerk der Speisen und Getränke’ (‘Masterpiece of Food and Drinks’) cannot be omitted here between the books by Hegenbarth (1899), Appelhans (1901) and Seutter (1909). (Not included is the literary presence of cocktails in Germany from the mid-19th century onwards, which were repeatedly described with admiration or disapproval in so-called Amerika Literatur due to massive emigration movements; more on this soon in this blog).

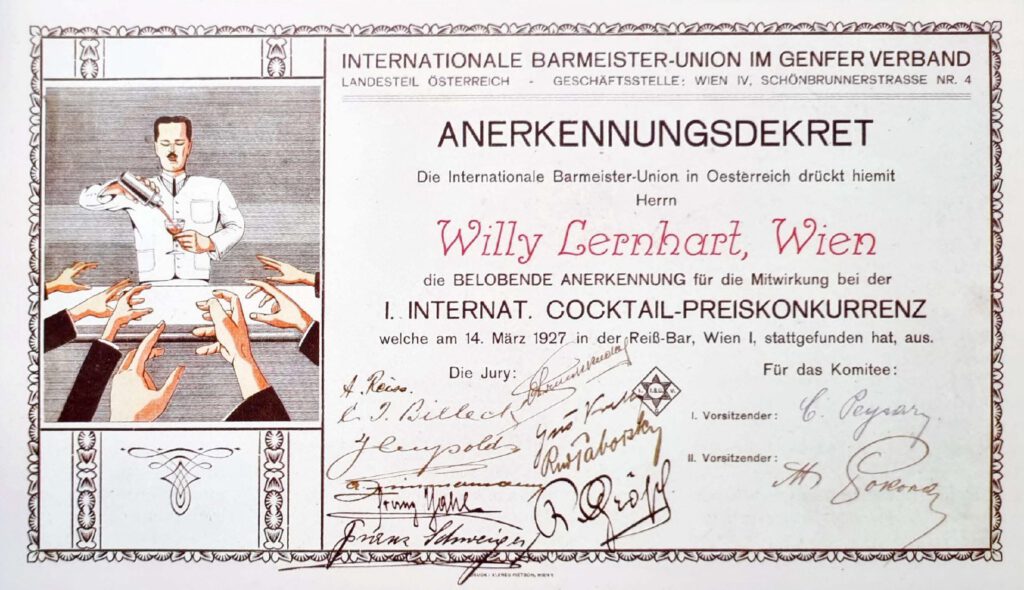

A turning point was the outbreak of the First World War in the summer of 1914, when ingredients became increasingly difficult to obtain. By the time the Americans entered the war in 1917, civilian travel to Berlin had also declined rapidly. As a result, Berlin’s bar scene suffered long-term, so that the ‘Golden Twenties’ were initially slow to take off in terms of cocktails. Nevertheless, Berlin bars experienced their heyday in the interwar period. Many bars became famous for their elegance and variety, such as the Eden Bar and the Kakadu Bar. Bienert impressively emphasises that women contributed to the atmosphere and economic success of the bars in a wide variety of roles. While the bars themselves are quite well documented, the bartenders and other protagonists are relatively hard to pin down, even in Berlin. Nevertheless, Bienert succeeds in giving some of them a stage.

‘In Berlin between the wars, we can observe that many bartenders frequently changed bars, only to work in better positions as their knowledge grew or to open a bar themselves at some point. This path is by no means unusual today either.’

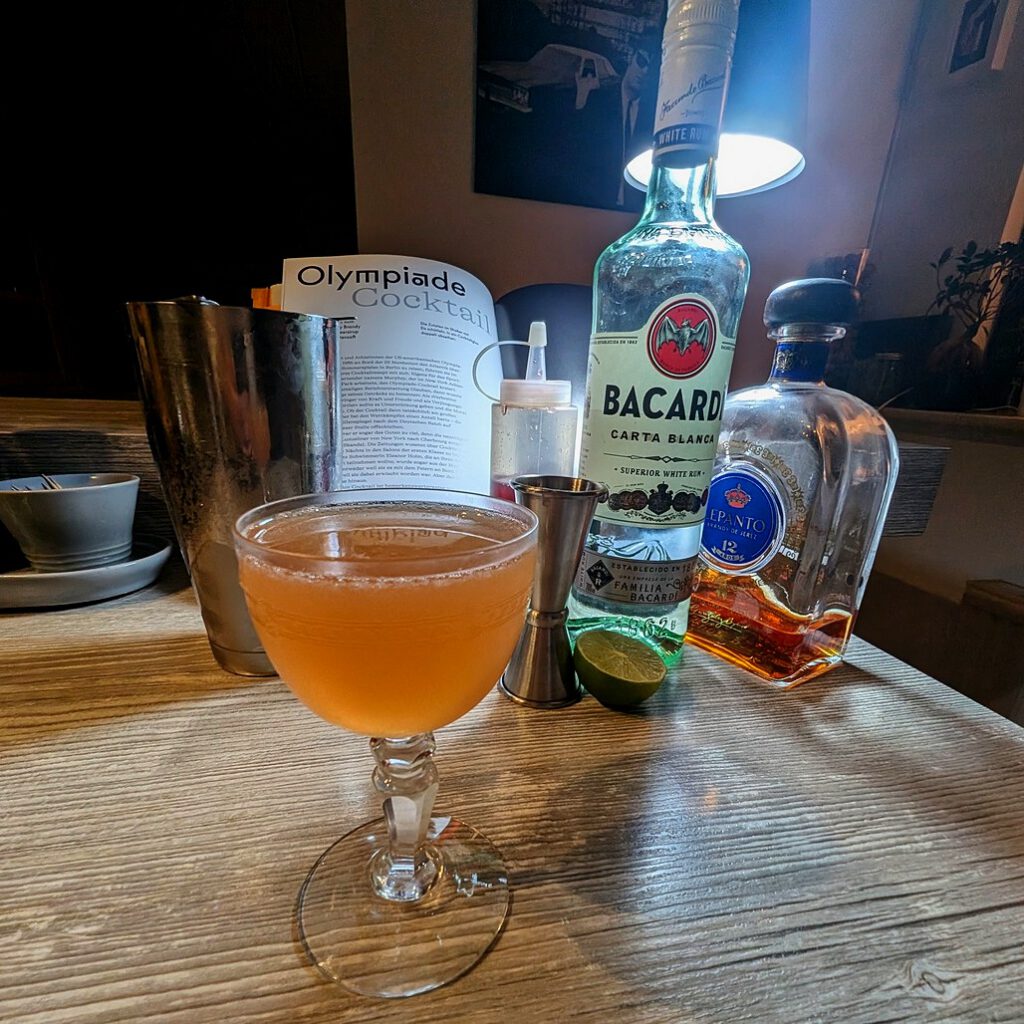

When the Nazis seized power in 1933, they did not take action against bars in principle, but they did against Jewish bar owners and musicians. Cocktails were therefore not wiped off Berlin bars with the first swastika flags. It was only during the 1936 Olympics in Berlin that the new rulers presented themselves as cosmopolitan for a brief interlude in the brown monotony. With the athletes from all over the world came new cocktails such as the Olympiade Cocktail and a thirsty clientele in the euphoric city. The years that followed saw the bars largely die out in the wake of racist and anti-Semitic small-mindedness. However, there were exceptions, such as the Greifi Bar, which survived the war. (Whether this was due to chance or calculated collaboration remains unclear).

Bars

The second part of the book consists of 15 profiles of current bars in Berlin, each with two double pages of photos and text. We learn details about the origin, decor, concept as well as special features and we also get to know the people behind the bar in brief. The selection is based on the author’s personal preferences, which fortunately means that even Berlin cocktail aficionados can discover unknown treasures that are not praised in every best list.

After the history section leaves us abruptly after the end of the Second World War, the presentations of the contemporary bars seem somewhat disparate in the context of the book. The oldest representatives, Green Door Bar and X-Bar, have been in existence since 1995, which still leaves a gap of 50 years in the narrative. Perhaps the compilation should be seen as a kind of subjective inventory of the year 2024, which Berlin barflies in particular will enjoy leafing through nostalgically in the future. Although Bienert doesn’t want to be ‘a tourist guide’, this section ultimately offers the rest of us in Germany a (well-made) bar guide that gives us an idea that our next visit to the capital will be a challenge for our livers and wallets. The remaining 13 bars are, in alphabetical order: Bar Zentral, Blacklist Bar, Buck and Breck, ČSA Bar, Fabelei, Galander Charlottenburg, The Gin Room, Hildegard Bar, Lang Bar, Stairs Bar, Velvet Bar, Victoria Bar[1] and Windhorst.

Recipes

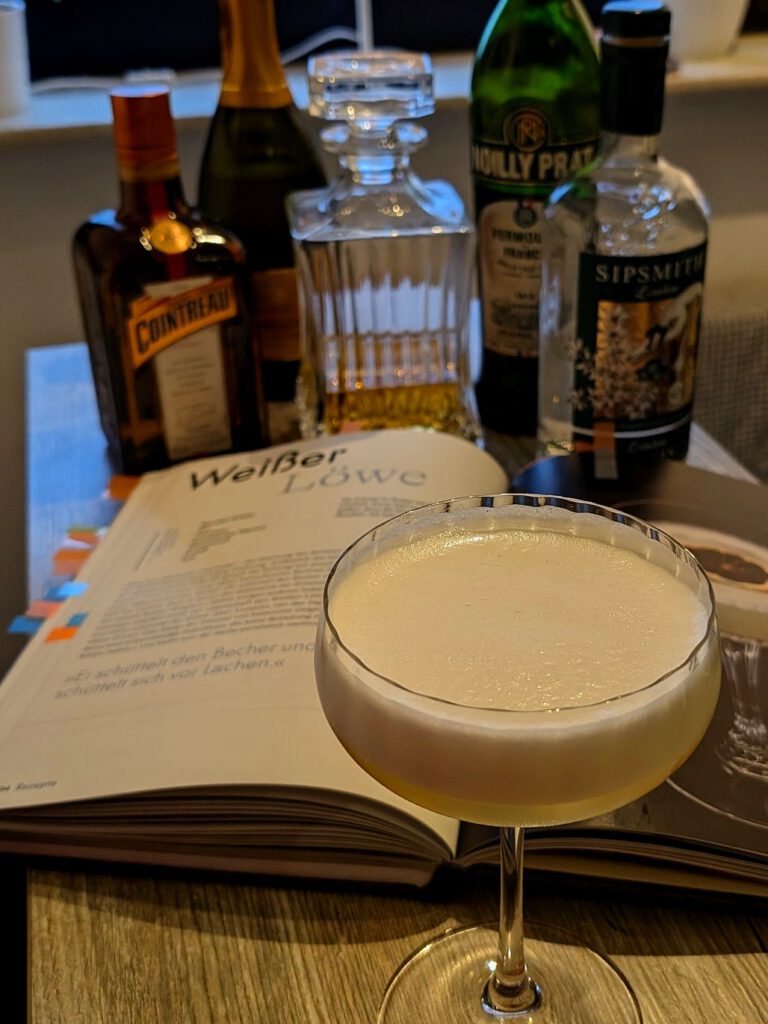

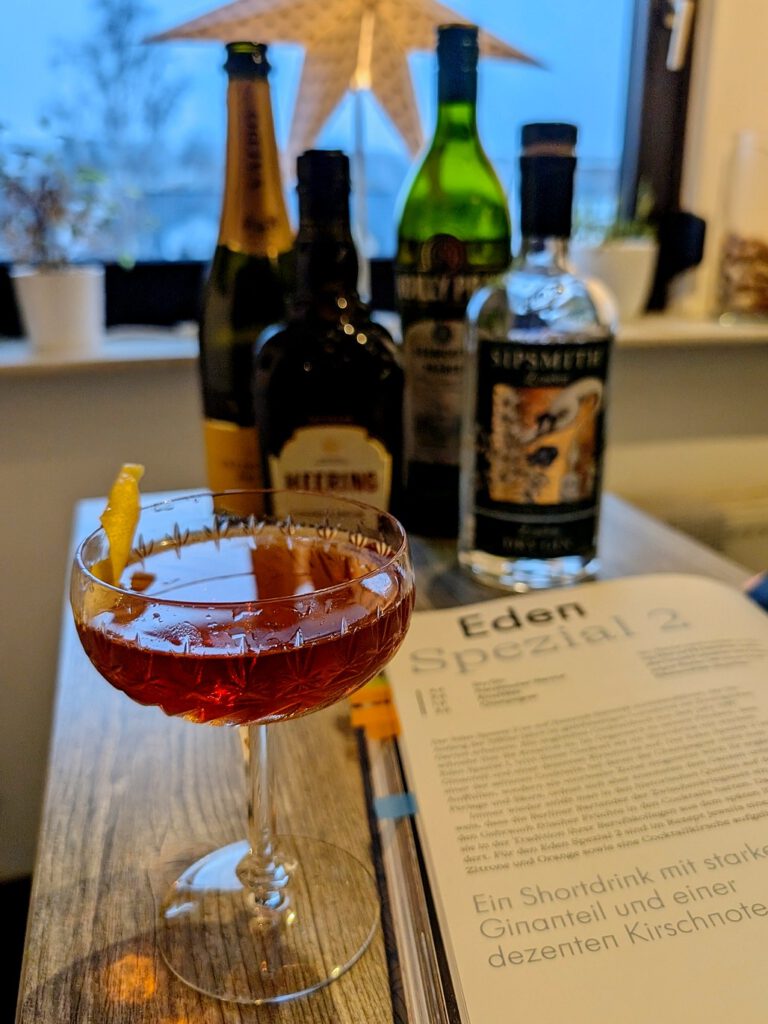

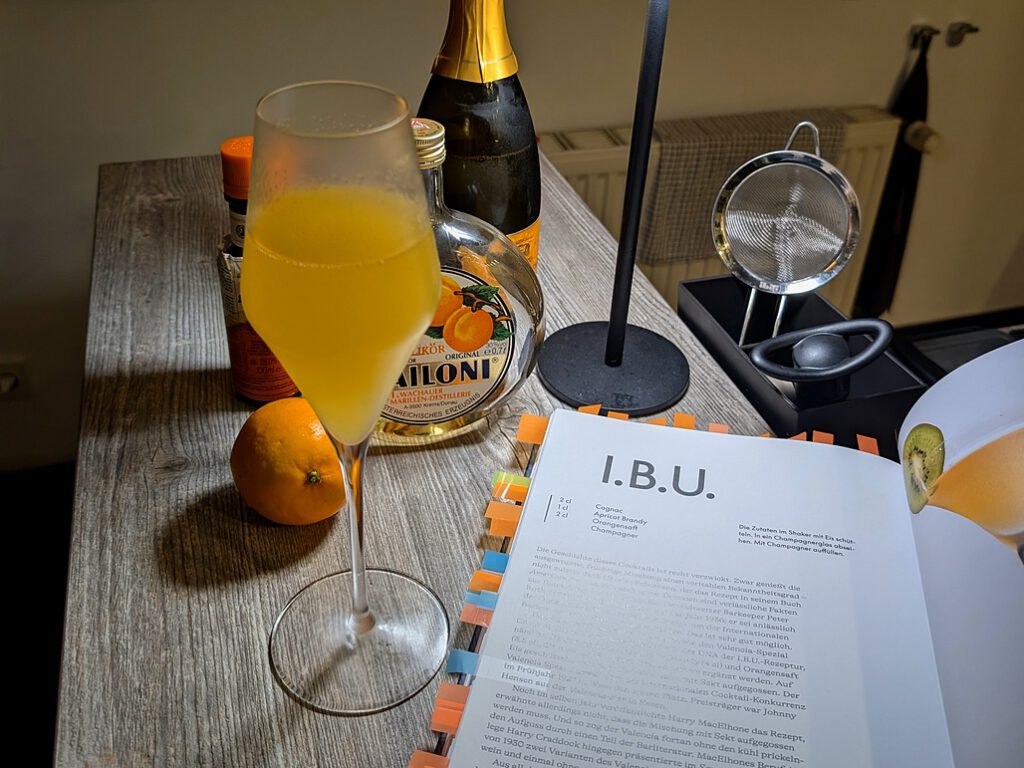

The collection of 50 cocktail recipes in the third part of the book links back to the story in the first part. A whole page is dedicated to each drink, often accompanied by a very appealing photo on the opposite page. In addition to the ingredients and preparation instructions, Bienert introduces us to the history of each cocktail with remarkable ease. This includes, on the one hand, the often nebulous origins of the drinks and, on the other – often much more exciting – their impact history: What went down particularly well with Berliners and what life of their own did drinks like Sidecar, Bijou and Corpse Reviver 2 develop on the Spree? Here and there you can also enjoy recreating classics in modified recipes by German bartenders from the interwar period. You get the feeling of breathing Berlin cocktail air when otherwise forgotten bartenders appear with their own (and sometimes quirky) creations, such as the Ohio Cocktail by Albert T. Neirath (1902), the Weißer Löwe (White Lion) by a certain Jonny (1928/29) or the Eden Spezial 2 by Heinrich ‘Heini’ Schmidt (1930s).

Although the Adlon was not the Hoffman House, Bienert gives a vivid impression of the cocktail flavour of the time. This sometimes seems unwieldy, but can also surprise and delight. It is not only German preferences that need to be taken into account, but also the range of products on offer: limes, for example, were often replaced by lemons, which were much more readily available. All in all, however, Berlin before 1945 was also closer to the spirit of the cocktail renaissance than the umbrella-covered juice shenanigans of the 1980s.

‘Time and again, historical sources point out that Berlin bartenders of the interwar period had a fondness for using fresh fruit in their cocktails. They were thus following in the tradition of their professional colleagues from the late 19th century.’

Michael C. Bienert is not a bartender, but seems to have done his homework well enough to be able to comment confidently on recipes and techniques. The order of the recipes did not quite make sense to me and I would probably have welcomed the recipes being interwoven with the historical account in order to contextualise them even better. On the one hand, however, this might have created great imbalances between the different time sections. On the other hand, it also makes it easier to use Bienert’s book as a classic cocktail book, in which you can browse through the recipes and be inspired to try them out. The silver German Cookbook Award 2024 from the cookbook portal kaisergranat.com certainly seems to confirm this.

Conclusion and outlook

From the perspective of this blog, the historical dimension of the book is particularly appealing and invaluable. While an archivist collects sources and artefacts, catalogues and categorises them, a historian creates a narrative about what happened and its causes and effects. Michael C. Bienert has succeeded in doing just that: He tells the story of cocktail culture in Berlin as part of history.

The presentation is unprecedented in this form and is likely to become the new gold standard for mixographers and cocktail historians. Only the work of the Czech bartender and historian Tomáš Mozr, who analysed the phenomenon of the American bar in the interwar period by comparing the cities of London, Berlin and Prague, already contains much that has found its way into Bienert’s book.[2] (The city map with the locations of the bars could have served as a model here). For Germany, there have otherwise been highly summarised outlines or detailed case studies (as in this blog). Bienert has relegated to the realm of fable the theses about Prohibition refugees or American occupation forces who are said to have brought the cocktail to Germany, as has been rumoured time and again. (Of course, exceptions prove the rule.)

The insights provided by ‘Cocktails in Berlin’ are by no means limited to the city on the Spree, as many of the developments described took a similar course throughout Germany and Europe. Berlin’s special role may be characterised by features such as the bodegas, the many American visitors, the strong female figures or the concentration of intellectuals and artists in the bars. But many things applied throughout Germany: the American bar began its triumphant advance in all cities around the turn of the 19th century; the First World War drove Americans out of the whole country; music and prostitution were associated with bars from Hamburg to Cologne to Munich and the ambivalence of the National Socialists in dealing with American bar culture was an all-German problem (for example, in the case of the Goldene Bar in Munich considered here). Against this background, cocktail historiography in Germany will have to take its cue from ‘Cocktails in Berlin’ for the foreseeable future and for good reason. (I strongly suggest the publication of an English version by Cocktail Kingdom or Ten Speed Press).

Above all, questions about the before and after remain unanswered: How did American mixed drinks arrive in Berlin? Did Great Britain, which had always been closely linked to the culture of the former overseas colony, play a mediating role? To what extent were ideas of and about cocktails already familiar before G. Arnoldi’s American Bar in emigration country Germany? Looking in the other direction: How did Berlin’s cocktail culture develop in the young Federal Republic? What role did the division of the city play? Did the East enthusiastically read ‘Wir mixen!’ (‘Let’s mix!’) from VEB Fachverlag in 1959? In the West, the early well-known names Franz Brandl and Charles Schumann (who are actually not so incredibly early) point to the Isar, not the Spree…

Michael C. Bienert himself does not fail to point out the incompleteness of his book, and his hints that he intends to provide a further instalment put me in a state of impatient anticipation.

Annotations

[1] The wonderful ‘Schule der Trunkenheit’ (‘School of Drunkenness’) by Kerstin Ehmer and Beate Hindermann from the Victoria Bar can be found in the bibliography, but due to its historiographical dimension it could also have been mentioned in the bar presentation (Berlin: Verbrecher Verlag 2022).

[2] Tomáš Mozr, American Bar – fenomén evropských metropolí: Londýn, Berlín, Praha. Příspěvek k dějinám barové kultury v západní a střední Evropě v meziválečném období [American Bar – Phenomenon of European Cities: London, Berlin, Prague. Contribution to the History of Bar Culture in Western and Central Europe between the Two World Wars], master thesis, Charles University Prague, Institute of World History 2015, esp. 65-94; cf. also Tomáš Mozr, The ‘exotic’ phenomenon of the American Bar in interwar Berlin and Prague: Re-reading the concept of place, in: AUC Geographica 54 (2019) 92–104, https://doi.org/10.14712/23361980.2019.9.