[German version | List of historical bars]

Contents:

- Part 1: The Führer gives the people of Munich a bar

- Hitler and art

- The House of German Art

- The “Golden Bar” 1937

- Wonderful world of wine – the bar’s picture programme

- The problem of interpreting internationality

- Part 2: Karl Heinz Dallinger, the painter of the “Golden Bar”

- Part 3: The “Golden Bar” during and after the war

- Cocktails in Hitler’s temple of art?

- Americans, carnivalists and critical deconstruction

- The Goldene Bar today and the legacy from back then

- Abbreviated references

Part 2: Karl Heinz Dallinger , the painter of the “Golden Bar”

[Estimated reading duration: 28 minutes]

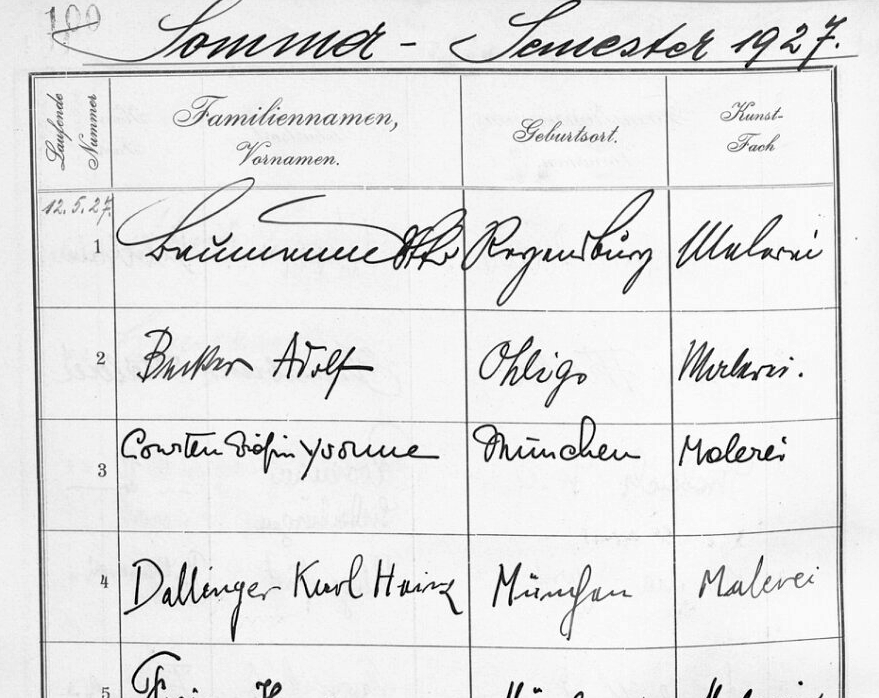

Karl Heinz Dallinger, the painter of the “Golden Bar”, was born in 1907 as the son of the painter Sigmund Dallinger, who specialised in glass painting.[59] From the summer semester of 1927 to 1932, Karl Heinz studied painting under Julius Diez at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich.[60] A graphic poster for a student ball from Dallinger’s days at the academy is circulating on the Internet, which is dated 1929.[61] He was also responsible for the interior design of student carnival parties called “Schwabylon” in 1929 and 1930.[62] The proximity to the artistic management of parties and bacchanalian gatherings, which was perhaps to culminate in the “Goldene Bar”, can thus be observed early on in Dallinger’s work. At the same time, his proximity to National Socialism is already evident: in March 1930, he was a member of the National Socialist German Students’ League and joined the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) in May 1933.[63] Two years later, the Nazi press gave a favourable assessment of the now 28-year-old Dallinger: “His ideological stance and firmness as well as his commitment to the National Socialist state: impeccable!”[64]

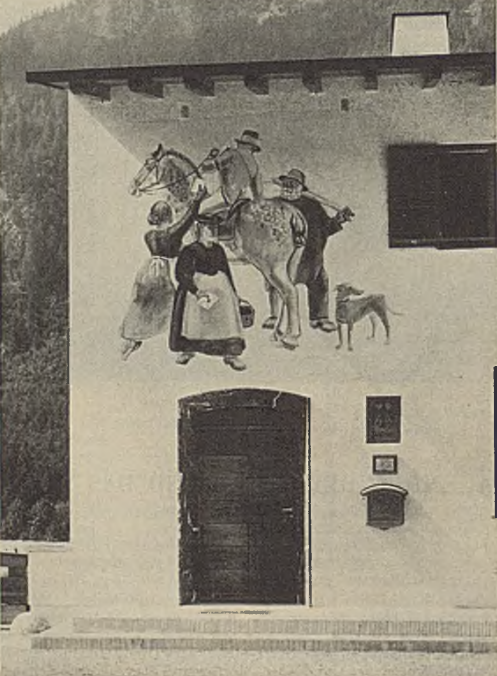

He initially made a name for himself artistically with frescoes on houses in Upper Bavarian mountain villages.[65] In Bayrischzell, for example, he designed the façade of the post office with a genre scene,[66] which is exemplary for other commissions on schools and other public buildings.[67] The proximity to traditional Bavarian Lüftlmalerei can be seen in his work, especially where he painted directly on the wall.[68] In 1937, Dallinger was appointed to the State School of Applied Arts in Nuremberg.[69]

In 1939, he was among the circle of artists and scientists who were elevated to the rank of professor by Adolf Hitler on the occasion of his 50th birthday.[70] In the same year, he moved to the Academy of Applied Arts in Munich as head of the decorative painting class.[71] After being drafted into the Wehrmacht in 1940, he worked as part of a propaganda company (PK) as a war artist in France, Russia and Sicily.[72]

In addition to his teaching activities, Dallinger worked as a freelance artist. He displayed a wide range of artistic techniques: In addition to painting in gouache and tempera, he created frescoes and mosaics – art forms that are, in principle, inseparable from the wall and the place where they are applied.[73] “The versatility of the still young artist”, praised a Nazi magazine for young people in 1939, “allows him to fulfil any task given to him, and his decorative art is already inseparably linked with the architecture of the Third Reich.”[74] Tapestries, which were called “Gobelins” after the French model from the 17th century, were a special art technique promoted by the Nazis. Although, as a typical form of representation of the Ancien Régime, they did not really fit in with the NSDAP’s emphatically bourgeois self-image, Hitler and the party leadership had discovered the tapestry medium to lend places and occasions a special dignity and gravitas. They were a favourite means of staging power. Karl Heinz Dallinger accepted numerous such commissions between 1936 and 1940.[75]

As a rule, the clients were not private individuals or companies, but Nazi institutions such as the Reichsschulungsburg of the German Labour Front (DAF) and the NSDAP in Erwitte[76] or the office of the NSDAP Gauleitung of the Hall of Honour on the Nazi Party Rally Grounds in Nuremberg.[77] On the cruise ship “Robert Ley” of the NS leisure organisation Kraft durch Freude (KdF), he was able to contribute a tapestry to the theatre hall.[78] A large group of works within Dallinger’s oeuvre were commissions for military institutions, among which the Luftwaffe in particular stood out with a large number of commissions for wall hangings in its bases and especially in officers’ messes.[79]

For a drink in the “Führerbau”

There are various accounts of how Dallinger was commissioned to paint the “Golden Bar” in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst.[80] But due to this success, Gerdy Troost commissioned him to paint murals in the “Führerbau”, which was opened in autumn 1937 as another major Nazi construction project.[81] The centre of the NSDAP in the “capital of the movement” was built on Königsplatz, the centre of Maxvorstadt.[82] In a prominent location on the east side of the square, Hitler was given a representative and official building in his capacity as head of the NSDAP, which, like the Haus der Deutschen Kunst, was originally designed by Paul Ludwig Troost.[83]

Inside, too, the design and layout of the rooms were tailored to the staging of power and in particular to the person of the “Führer”: The piano nobile was reserved for him: He had his office (1) above the right-hand entrance to the building, from where he could step out onto the balcony if necessary and address the crowds gathered on Königsplatz via a loudspeaker system.[84] Along the same corridor on the north side of the street was a series of rooms that were initially intended for Hitler’s deputy Rudolf Hess, but were then designed as a representative extension of the “Führer‘s” rooms for the reception of important guests:[85]

An elongated hall called the “Wandelhalle” (2), which was intended to serve as a social room, was adjoined by a spacious smoking room (3) and finally, in the north-west corner of the 1st floor, a bar (4). Typical furnishings such as a glass ware cabinet, bar table and bar stools could be found here,[86] but there was also a surrounding bench and bistro tables with chairs arranged similarly to the “Golden Bar”. However, there was no provision for a dance floor in the centre of the room or space for musicians. Access to the area behind the bar was apparently via a second entrance to the east through a utility room with crockery cupboards and sinks as well as a dressing room (5). In the basement of the “Führerbau”, attached to the canteen kitchen, there were cold storage rooms where raw ice could be made and brought in directly via a service lift.[87]

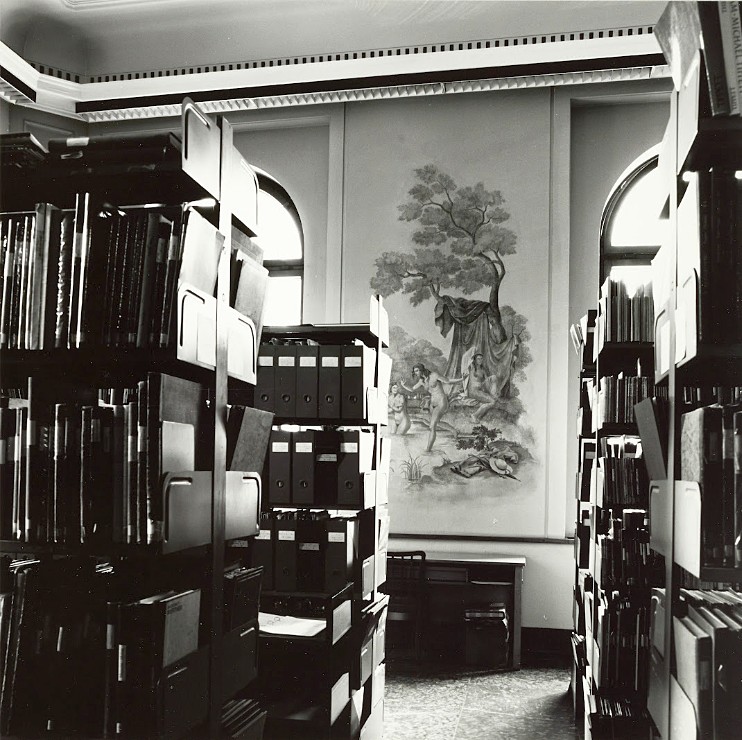

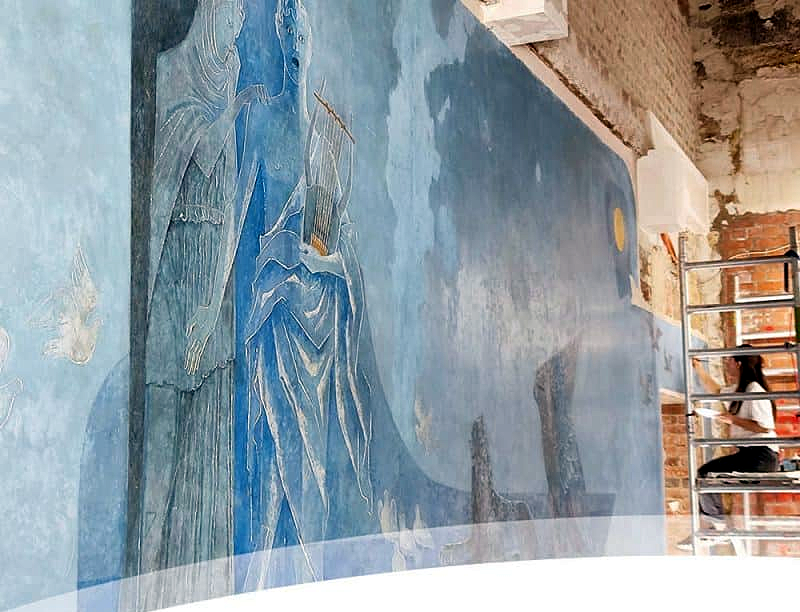

The murals in the bar were painted by Karl Heinz Dallinger in 1939. He painted allegories of the four seasons in bright colours on the white wall panels between the windows and doors of the square room: people working in the garden represent spring, naked bathers represent summer and people picking apples represent autumn. Winter is represented by three carnival witches dancing around a tree in the snow.[88] Above the two lintels are flying cranes and a pergola with vines.[89] The “Führerbau” has housed the University of Music and Performing Arts Munich since 1957, and the murals can still be found in its library. They were cleaned in 1977 as part of general renovation work.

However, until his death in 1997, Karl Heinz Dallinger denied that the paintings were his.[90] In fact, they differ stylistically from his other works: the figures are more dynamic and animated. His otherwise recognisable tendency to avoid perspective and spatiality,[91] is also absent from the skilfully created scenes. On the other hand, in post-war Germany he could have had a strong interest in not being associated with works directly related to Adolf Hitler. This applied all the less to the “Golden Bar”, as the murals there spent their existence hidden under plywood panels from the mid-1950s onwards. What is certain is that Dallinger specialised in sweetening Nazi celebrations with his paintings,[92] and that the “Führer” had a bar set up in his official residence in Munich. In contrast to the “Golden Bar”, which was open to everyone, the bar in the “Führerbau” was reserved for high-ranking party functionaries and guests of honour. As Hitler rarely used the building and only held a few receptions here,[93] the bar is more likely to have been used by Rudolf Hess and his successor Martin Bormann, who had their office here on the second floor,[94] and their staff.

Decorator of power

At the Großen Deutschen Kunstausstellungen (GDK – Great German Art Exhibitions) in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst, Dallinger was mostly represented with individual exhibits. 1943 was by far his most successful year, as he was represented with nine drawings and five paintings in two halls. In this year, he was also able to sell works to elites of the Nazi regime, such as the notorious Düsseldorf Gauleiter Friedrich Karl Florian.[95] Three further works were purchased by Albert Speer, Hitler’s close confidant and favourite architect. This was particularly attractive for Dallinger, as Speer not only collected art in his capacity as a private individual, but had also repeatedly purchased and compiled art for the “Führer’s” building projects on his personal behalf, for example for the Berghof, Hitler’s retreat on the Obersalzberg in Upper Bavaria, and for the New Reich Chancellery in Berlin.[96] Apart from the saleable exhibits, a number of Dallinger’s paintings were lent to Munich on the occasion of the GDK and were owned by illustrious institutions such as the new building management of the Wehrmacht High Command,[97] the Luftgaukommando XI Hamburg[98] or the Reich Aviation Ministry.[99]

While Dallinger was represented with Mediterranean landscapes, among other things,[100] the museum also exhibited works by him that unmistakably conveyed the National Socialist self-image: as a “Decorative picture for the Luftwaffe officers’ mess”, the opening exhibition in 1937 included a picture in the same technique that he had also used in the “Golden Bar”: the NSDAP emblem, the eagle with the swastika emblem in its claws, was emblazoned across a gold background (illustration here). A Hitler quote from 1936 was inscribed in large letters: “We are one people and no one can break it. We will remain one people and no world will ever conquer us.”[101] Dallinger also executed the motif in a similar form as a tapestry for the Air District Command V in Munich.[102]

The swastika eagle was also prominently displayed on a mosaic based on Dallinger’s design, which was exhibited at the International Crafts Exhibition in Berlin in 1938: The topographical outlines of the German Reich after the “incorporation” of Austria were emblazoned on the front of an idealised “German” ballroom, illustrated with nationally significant landmarks,[103] very similar to the principle of the wine landscapes in the “Golden Bar”. Dallinger used the motif of the swastika eagle at least seven times in different techniques and variations.[104] The artist benefited from the fact that official buildings were required to display the national emblem, although standardised reproductions could not be used.[105]

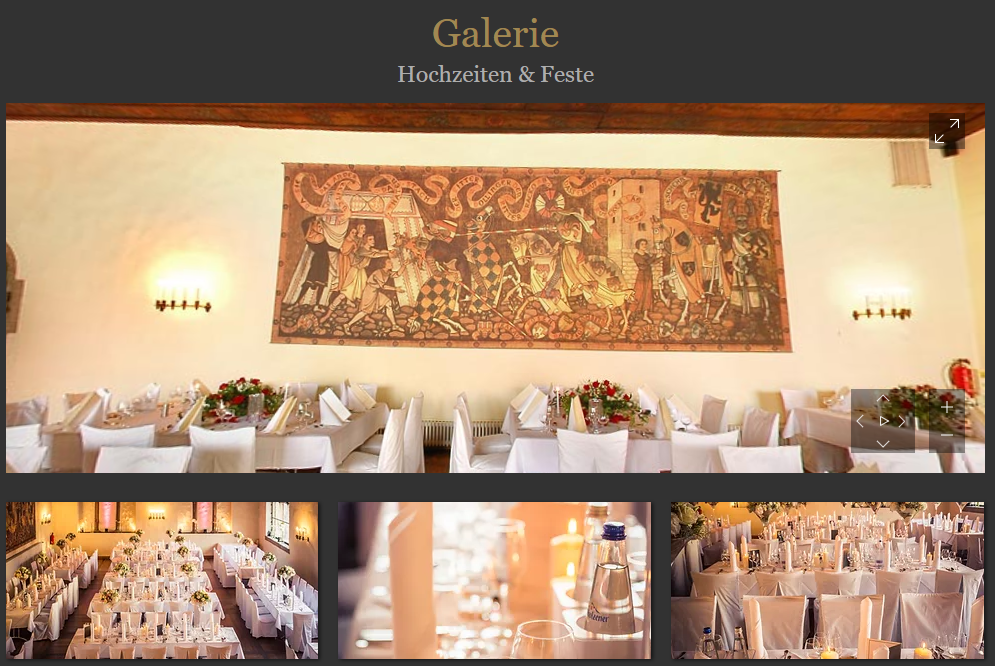

The National Socialist view of the world and the glorification of the brutal grasp for world power could also take on more subtle forms that are apparently still acceptable today, as another exhibit at the GDK shows: a huge tapestry with variations on motifs from the Codex Manesse,[106] the most extensive and famous German song manuscript of the Middle Ages, superficially emphasises the supposed greatness of German history.[107]

Depicted is the key scene of the so-called Dollinger saga with its climax, the dramatic defence against the pagan knight Kracko by Hans Dollinger, a citizen of Regensburg sent by King Henry I.[108] The Regensburg Nazi district cultural administrator and museum director Walter Boll had commissioned the tapestry in 1940 for the hall of the medieval Herzogshof , which had been radically remodelled under his aegis from 1937.[109] On closer inspection, the scene reveals unmistakable contemporary references to Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939. In the lower field of the picture are the names and coats of arms of conquered cities that were considered German, such as Kraków (“Krakau”), Poznań (“Posen”) and Gdańsk (“Danzig”). In addition, the victorious soldier on the right is wearing stylised swastikas on his shield and armour, which appear to be made of flower petals.

Fig. left: Dollinger versus Kracko (detail), photo: Peter Morsbach, Regensburg als Denkmal deutscher Geistes, in: Arbeitskreis Regensburger Herbstsymposion (ed.), “Zum Teufel mit den Baudenkmälern”. 200 Jahre Denkmalschutz in Regensburg, Regensburg: Dr Peter Morsbach 2011, 33.

The medieval legend of the citizen Dollinger, who was imprisoned and only released to save the realm (German: Reich), could be reinterpreted as National Socialist iconography on another level against the backdrop of Hitler’s biography and self-image: the “Führer” wrote large parts of his programmatic pamphlet “Mein Kampf” during his imprisonment in Landsberg Fortress in 1924 and subsequently wrote his personal political success story – which became the greatest catastrophe in human history. A full-size copy of the original Dallinger-Dollinger carpet still hangs in the Herzogssaal, which today is mainly used as an event and wedding location.[110] [See UPDATE 16.09.2024]

Until 1945, Karl Heinz Dallinger showed no reservations about National Socialism, neither in his biography nor in his oeuvre – on the contrary: a large group of his works clearly show propagandistic traits. “In a large number of subjects, he was one of the obvious ideologues among the artists. In this respect, Dallinger […] was a devoted decorator of power.”[111] If one adds to this the works without an overtly political message, but which belonged in politically and symbolically charged contexts – the paintings in the bar of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst must be counted as such – then non-political paintings for private contexts form a minority. In Dallinger, the “movement” had found a convinced representative who – had he achieved greater fame as an artist – would have had to be regarded as a formative shaper of the aesthetics of National Socialism.

Looking past the politics, Dallinger’s special relationship with celebrations is evident from the outset. His works are strikingly often associated with catering, casinos, dining and banqueting halls as well as festive occasions. Alcohol is an essential element either through the choice of motifs or through the functional or spatial contexts of the pictures. In this respect, his most famous work then and now, the “Golden Bar”, may have been a special affair of the heart, whose sincere enthusiasm can unfold its effect beyond all politics and atrocities.

A cocktail shaker for Siemens: Dallinger after 1945

Karl Heinz Dallinger survived the war and subsequently continued to work as a freelance artist. He was once again able to secure commissions for wall paintings and carpets as well as mosaics, particularly in the 1950s.[112] His works, some of whichcan still be seen in situ, such as the “Golden Bar”, include the mosaics on the gables of the side wings of Stuttgart’s St. Eberhard church, which were added in 1955,[113] four paintings in the parquet foyer of the Düsseldorf Opera House (1956),[114] the large Orpheus painting in the foyer to the balcony hall of the Bayreuth Stadthalle (1957), which has already survived various renovation works,[115] or a tapestry in the boardroom of Deutsche Bank in Düsseldorf (1957).[116]

The list of commissions seems like a continuation of Dallinger’s activities before 1945, only under the auspices of the Federal Republic of Germany. This need not always have happened by chance: For example, when he executed the stone mosaic “Earth” for the Technical School of the newly founded German Air Force (TSLw 2) in Lagerlechfeld in 1956,[117] there were probably men working in the command staff who, like the commissioned artist, could look back on professional experience before 1945. It is possible that contacts from Dallinger’s numerous works for the Third Reich Luftwaffe still existed here.

Professor Dallinger, as he continued to be known, was almost involved in designing the operational heart of the young democracy: In 1950, the “Expert Committee for Questions of the Fine Arts”, which was set up under the Federal Minister of Finance,[118] launched a competition in 1957 to decorate the plenary chamber of the Bundesrat in Bonn. Three artists – including Dallinger – were invited to submit designs on the theme of “The Law” for the anteroom.[119] However, in the eyes of the jury, the works received did not result in “a solution that was appropriate for the space and satisfactory for today’s artistic sensibilities”.[120] The contract was awarded to textile artist Edith Müller-Ortloff with her now lost tapestry “Farbfuge”.[121]

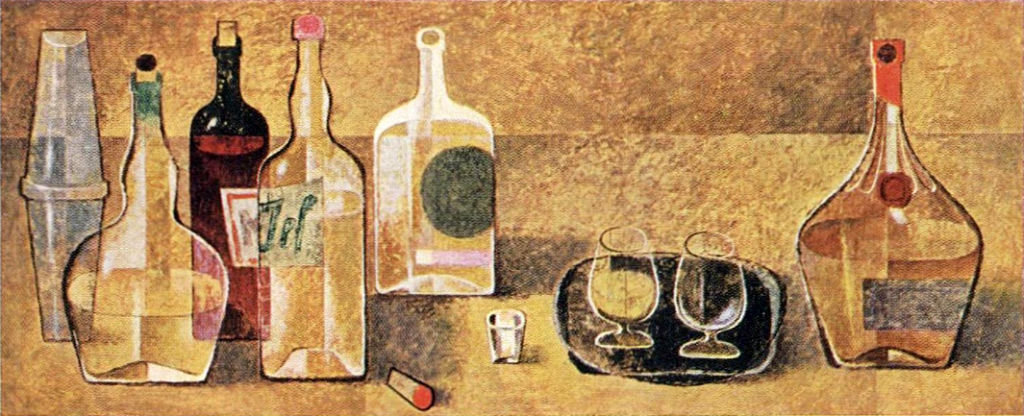

One of Dallinger’s successfully completed commissions in post-war Germany deserves special mention: in 1959, he was able to help design the casino hall of the new Siemens building on Lindenplatz in Hamburg,122] for which he created a series of individual paintings. The different formats are scattered randomly across the white surface of one wall of the casino. In keeping with the purpose of the space, they contained still life motifs on the theme of food and drink. In a cubist-influenced manner, one of the pictures showed five bottles of spirits, two cognac swirlers on a tray, a shot glass, a loosened cork and, on the left-hand edge of the picture, a cocktail shaker, more precisely a tin-in-tin Boston shaker.[123] With a delay of 20 years, there is a clear reference to cocktail culture here, which the décor of the “Golden Bar” lacks. Unfortunately, the alcoholic still life is now lost. The casino on the top floor of the Siemens building in Hamburg was replaced by a canteen on the ground floor in the 1980s.[124]

After the war, Dallinger not only remained true to the close relationship between wall, image and space, but also to his preference for designing places of celebration and drinking:

“One can sense from the pleasurable execution and the relaxed, cheerful mood of these still lifes that they were among the commissions that gave Dallinger the greatest pleasure and that were received with just as much joy by the client.”[125]

The friendly judgement of fellow artist Wolfgang Christlieb on the works in the Siemens House appeared in 1960 in the magazine “Die Kunst und das schöne Heim”, which had still reported on Dallinger’s works under the name “Die Kunst für Alle” during the Third Reich. It continued to be published by the Munich-based Bruckmann family, who had made a name for themselves as early supporters of Hitler. As mentioned, they had introduced the later “Führer” to the architect Troost, in whose buildings Dallinger was allowed to decorate the bars.

The artist also pursued a regular job in West Germany: He initially worked as a teacher of textile design at the Schachenmayr, Mann & Co worsted yarn spinning mill in Salach near Göppingen, later taking over as head of the advertising department and even becoming managing director of the company in 1981 at the age of 74, which celebrated its 200th anniversary in 2022. Karl Heinz Dallinger died on 2 May 1997 in Munich.[126]

Like Dallinger, the House of German Art continued to exist after the war. Unlike many a Nazi after 1945, however, the name change here did not serve to conceal its own role in the Third Reich.

UPDATE 16.09.2024

According to a report by the online magazine regensburg-digital.de from 4 September 2024, the Dallinger-Dollinger carpet was recently taken down following a request from two city council members. The event location Herzogsaal is operated by the company Pro Gastro GmbH as a tenant. The owner of the building is Domplatz 3 und Kornmarkt 10 GmbH & Co. KG, which acquired the building in 2002. According to the company, the carpet could not be removed until now due to a ‘condition imposed by the Monuments Office’. Furthermore, in 2003 the tapestry was replaced by the most recently exhibited copy due to a requirement of the Bavarian State Office for the Preservation of Monuments: ‘In order to protect the tapestry (e.g. from cigarette smoke/catering use), the tapestry should either hang behind a glass display case or a copy should be attached’. According to the city of Regensburg, the State Office was also responsible for the fact that there had been ‘no possibility of arranging for the removal’ of the copy to date. The current owners had donated the original carpet to the museums of the city of Regensburg. Historians had been pointing out the problematic provenance and symbolism of the carpet in the Herzogsaal since at least 2011 in publications, some of which were issued by the Regensburg Monuments Office. (The current events had attracted a certain amount of media attention, in the course of which the above statements from ronnenbar.de were quoted several times).– Lisa Schnell, „Heiraten unterm Hakenkreuz“, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung. 15.09.2024, https://www.sueddeutsche.de/bayern/regensburg-nazi-teppich-hakenkreuz-herzogssaal-eventlocation-denkmalschutz-lux.BMbVS2rn7EWBX11DQcrCXH (16.09.2024); Stefan Aigner, In Regensburg huldigt ein Wandteppich dem Nazi-Überfall auf Polen – jetzt kommt er runter, in: Merkur.de, 08.09.2024, https://www.merkur.de/bayern/regensburg/in-regensburg-huldigt-ein-wandteppich-dem-nazi-ueberfall-auf-polen-jetzt-kommt-er-runter-93285945.html (16.09.2024); Regensburger Nazi-Teppich wird abgehängt – unrühmliche Rolle des Denkmalschutzes, in: regensburg-digital.de, 04.09.2024, https://www.regensburg-digital.de/regensburger-nazi-teppich-wird-abgehaengt-unruehmliche-rolle-des-denkmalschutzes/04092024/ (16.09.2024); Stefan Aigner, Heiraten unterm Hakenkreuz – in Regensburgs Herzogssaal ist’s möglich, in: regensburg-digital.de, 22.08.2024, https://www.regensburg-digital.de/heiraten-unterm-hakenkreuz-in-regensburgs-herzogssaal-ists-moeglich/22082024/ (16.09.2024).

◄ Part 1: The Führer gives the people of Munich a bar

Part 3: The “Golden Bar” during and after the war ►

[Translated from German with the help of deepl.com.]

Annotations

[59] Schmidt 2012, 310.

[60] Karl Heinz Dallinger, in: Matrikelbuch 5, 1919-1931, 100, https://matrikel.adbk.de/matrikel/mb_1919-1931/jahr_1927A/matrikel-0004 (28 Dec. 2023). Schmidt 2012, 310, gives 1928. Cf. also Julius Dietz, in: Matrikelbücher, Lehrer, https://matrikel.adbk.de/lehrer/diez-julius (10 March 2024); Prölß-Kammerer 2000, 93 ff.

[61] Hartewig 2018, 138.

[62] Art. Münchner Fasching, in: Münchner neueste Nachrichten. Wirtschaftsblatt, alpine und Sport-Zeitung, Theater- und Kunst-Chronik 82. Jahrgang, No. 42, 12.02.1929, 6, https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/view/bsb00133780_00259_u001?page=6,7 (09.02.2024); Art. Prinz Karneval still reigns, in: ibid., 83rd year, no. 48, 4, https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/view/bsb00134807_00413_u001?page=4,5 (09.02.2024).

[63] Hartewig 2018, 138 f.

[64] The Kunstkammer. Illustrierte Monatszeitschrift mit amtlichen Mitteilungen, 1st vol. (1935) H. II; cited in Hartewig 2018, 139 (translated from german); Prölß-Kammerer 2000, 95.

[65] Heilmeyer 1938, 314 ff; Jugend Nr. 2, 10 Jan. 1939, 23 (http://www.jugend-wochenschrift.de/uploads/tx_lombkswjournaldb/pdf/2/44/44_02.pdf (28 Dec. 2023); cf. Brantl 2007, 55.

[66] J. Hoffmann, Kunst und Kunsthandwerk am Bau: 233 Arbeiten in Stein, Eisen, Holz und anderen Werkstoffen, Stuttgart: J. Hoffmann 1937, 79; Robert Pöverlein, Die bauenden Behörden und das Handwerk, in: Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung vereinigt mit Zeitschrift für Bauwesen. Mit Nachrichten der Reichs- und Staatsbehörden, vol. 54, no. 19, 250, https://delibra.bg.polsl.pl/dlibra/publication/26548/edition/24397/content (10 February 2024).

[67] Hartewig 2018, 138.

[68] Cf. Christoffel 1941, 172/176 (translated from german): “Sources of folk art that have run dry are rediscovered from good heritage through this type of wall decoration.”

[69] Dallinger, Karl Heinrich, in: Nürnberger Künstlerlexikon: Bildende Künstler, Kunsthandwerker, Gelehrte, Sammler, Kulturschaffende und Mäzene vom 12. bis zur Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts, ed. by Manfred H. Grieb, Munich: K. G. Saur 2007, 238. – Schmidt 2012, 310, knows of a teaching position for decorative painting at the same institution from 1935. The information does not necessarily contradict each other.

[70] Cf. e.g. Künstler und Wissenschaftler werden geehrt, in: Münsterischer Anzeiger – Westfälischer Merkur – Münsterische Volkszeitung. Amtliches Organ des Gaues Westfalen-Nord der NSDAP und sämtlicher Behörden, 88th edition, 20 April 1929, https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/newspaper/item/PUZTZZBEVTAYQUQ5AWPXKDOVIVFYPGVM?tx_dlf&issuepage=2&fromDay=7&toYear=1968&fromYear=1937&toDay=2&toMonth=3&fromMonth=1&sort=sort.publication_date+asc&page=4&hit=5 (11 February 2024).

[71] Jugend Nr. 2, 10.01.1939, 23, http://www.jugend-wochenschrift.de/uploads/tx_lombkswjournaldb/pdf/2/44/44_02.pdf (28.12.2023); Junge Kunst im Deutschen Reich, Vienna 1943, 27, https://archive.org/details/JungeKunstImDeutschenReich1943_123/page/n27/mode/2up (12.02.2024).

[72] Junge Kunst im Deutschen Reich, Vienna 1943, 27, https://archive.org/details/JungeKunstImDeutschenReich1943_123/page/n27/mode/2up (12 February 2024). Cf. Schmidt 2012, 310.

[73] Nazi art policy propagated wall painting; see Schwarz 2011, 209. Christoffel 1941, 171, enthused about the “imagery under the guidance of architecture” (translated from german).

[74] Jugend No. 2, 10 January 1939, 23, http://www.jugend-wochenschrift.de/uploads/tx_lombkswjournaldb/pdf/2/44/44_02.pdf (28.12.2023) (translated from german).

[75] Hartewig 2018, 140. Cf. ibid. 114 (translated from german): “Art that was created in the Third Reich was to a large extent commissioned art. And it was applied art. For ideological reasons, arts and crafts were also held in high esteem.” On tapestries in the Third Reich cf. Prölß-Kammerer 2000.

[76] Hartewig 2018, 139.

[77] Hartewig 2018, 140; Prölß-Kammerer 2000, 70 ff.

[78] Jugend No. 20, 16 May 1939, 386, http://www.jugend-wochenschrift.de/uploads/tx_lombkswjournaldb/pdf/2/44/44_20.pdf (19.02.2024); cf. Hartewig 2018, 142; Prölß-Kammerer 2000, 217.

[79] Hartewig 2018, 113, 139 f.

[80] Brantl 2007, 55, with reference to Heilmeyer 1938, 314 ff. (translated from german): “The golden mural was painted by Karl-Heinz Dallinger, with whom Mr and Mrs Troost had been acquainted since the 1920s” (Dallinger was still a student). – Haus der Kunst, Ihr Besuch, Goldene Bar, https://www.hausderkunst.de/ihr-besuch/goldene-bar (05.03.2024) (translated from german): “at the suggestion of Ernst Haiger, the bar’s architect”. – Görl 2010 (translated from german): “Competition for the design of the wine bar”. – Hartewig 2018, 142 (translated from german): “This circumstance suggests a close collaboration with the star architect of the movement Paul Ludwig Troost, who died at an early age, which may have been continued after his unexpected death in 1934 with the “Atelier Troost” under the direction of his widow, Gerdy Troost.”

[81] Krause 2012, 31, 40; Schwarz 2011, 179.

[82] Krause 2012, 27 ff.

[83] Krause 2012, 29, 32.

[84] Krause 2012, 37. The Haus der Deutschen Kunst also had comparable devices; see Brantl 2007, 53.

[85] Seckendorff 1995, 131, 133 f.

[86] Seckendorff 1995, 138.

[87] Krause 2012, 40; Seckendorff 1995, 142.

[88] Hartewig 2018, 142.

[89] According to Hartewig 2018, 142, the pictorial decoration of the bar remained unfinished because Dallinger was drafted into a propaganda company in 1940.

[90] Seckendorff 1995, 139, note 105. Against this background, it is also not credible that Dallinger, with regard to his work in the “Goldene Bar”, “tinted that Hitler himself had taken care of the matter” (Görl 2010) (translated from german).

[91] Schmidt 2012, 310.

[92] In the basement of the “Führerbau” there was a casino, which Ernst Haiger and Karl Heinz Dallinger were also involved in designing; see Seckendorff 1995, 142. The two also collaborated on the “Haus Tannhof” in the Harlaching district, which was opened in 1938 as a guest house for the city of Munich. Dallinger also painted murals in the Munich Künstlerhaus on Lenbachplatz, which was initially brought into line by the Nazis and was ultimately ordered to be demolished by the “Führer”; Jugend Nr. 2, 10 Jan. 1939, 23 (http://www.jugend-wochenschrift.de/uploads/tx_lombkswjournaldb/pdf/2/44/44_02.pdf (28 Dec. 2023); see Schmidt 2012, 310.

[93] Krause 2012, 36.

[94] Krause 2012, 33 ff., 42 f.

[95] GDK Research, https://www.gdk-research.de, GDK1943-A-0079.

[96] Schwarz 2011, 176 f., 189. On Speer’s collecting activities Petropoulos 1999, 290 ff. On purchases by members of the NSDAP leadership Brantl 2017b, 184.

[97] GDK Research, https://www.gdk-research.de, GDK1940-0178, GDK1940-0179.

[98] GDK Research, https://www.gdk-research.de, GDK1942-0174.

[99] GDK Research, https://www.gdk-research.de, GDK1943-A-0078.

[100] W. P. Schulz, Umgruppierung im Haus der Deutschen Kunst, in: Die Kunst für alle: Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur 59, Munich: F Bruckmann 1944, 82, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/kfa1943_1944/0125/image,info (11/03/2024).

[101] GDK Research, https://www.gdk-research.de, GDK1937-0112. Cf. speech on the Reichserntedankfest 1936, in: Frankenberger Tageblatt, 05.10.1936, 1, https://sachsen.digital/werkansicht/438568/1 (19.02.2024) (translated from german); cf. Schmidt 2012, 75.

[102] Kunsthandwerk auf der Münchener Ausstellung, in: Innendekoration. Mein Heim, mein Stolz. Die gesamte Wohnungskunst in Bild und Wort, no. 49, 1938, 159 and 171, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/innendekoration1938/0185/image,info (19 February 2024); Prölß-Kammerer 2000, 97.

[103] Ellie Tschauner, Handwerk aus aller Welt. von der internationalen Handwerks-Ausstellung in Berlin, in: Innendekoration. Das behagliche Heim 49, Darmstadt & Stuttgart: Alexander Koch 1938, 342 f., https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/innendekoration1938/0356/image,info (11.03.2024); Robert Pöverlein, Die Raumgestaltung auf der Internationalen Handwerks-Ausstellung in Berlin, in: Der Baumeister 36, Heft 8, August 1938, https://delibra.bg.polsl.pl/dlibra/publication/21281/edition/19738/content (11.03.2024); cf. Prölß-Kammerer 2000, 128 ff.

[104] Cf. Hartewig 2018, 142

[105] Büttner 2011, 12.

[106] GDK Research, https://www.gdk-research.de, GDK1941-0169.

[107] Codex Manesse, in: Wikipedia. Die freie Enzyklopädie, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex_Manesse (11.03.2024).

[108] Dollinger saga, in: Wikipedia. Die freie Enzyklopädie, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dollingersage (11 March 2024).

[109] Walter Boll, Bolls Wirken im Nationalsozialismus, in: Wikipedia. Die freie Enzyklopädie, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Boll#Bolls_Wirken_im_Nationalsozialismus (11 March 2024).

[110] Eugen Trapp, Walter Boll und die Vision vom autogerechten Mittelalter – oder: die verkehrsplanerische Dimension Schöpferischer Denkmalpflege in Regensburg, in: Arbeitskreis Regensburger Herbstsymposium (ed.), Alte Stadt und moderner Verkehr – Konflikte und Konzepte aus drei Jahrhunderten, Regensburg: Peter Morsbach 2020, 51 f.

[111] Hartewig 2018, 143 (translated from german); see also Van der Will 1995, 107: “Those who were excluded from that vision [sc. des Dritten Reichs] were to be enslaved and exterminated, but those included were promised a bright future as a racially pure and culturally harmonious community. Contemporary German artists, among them Karl Heinz Dallinger, illustrated this idea in allegorical pictures.”

[112] Schmidt 2012, 310; cf. Prölß-Kammerer 2000, 255, note 491.

[113] Catholic parish of Stuttgart-Mitte, Cathedral Church of St Eberhard, https://www.kath-kirche-stuttgart-mitte.de/gemeinden/st-eberhard/domkirche-st-eberhard (11 March 2024); Hartewig 2018, 143.

[114] Opernhaus mit Lichtkugel. Bild soliden Reichtums in der neuen Düsseldorfer Bühne, in: Honnefer Volkszeitung, 25 April 1956, 3, https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/newspaper/item/SMJVWQEFCACKTIX2DGHY2JTCSZHPIRRX?issuepage=3 (11 March 2024); Opernhaus Düsseldorf, Innenarchitektur, in: Wikipedia. Die freie Enzyklopädie, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opernhaus_D%C3%BCsseldorf#Innenarchitektur (11 March 2024).

[115] Dallinger apparently received the commission through the Bayreuth architect Hans Reissinger, who was called “the little Speer” during the Nazi era; see Michael Weiser, Dunkle Vergangenheit. Die Stadthalle mal jenseits des “Guten und Schönen”, in: Kurier, 06.09.2013, https://www.kurier.de/inhalt.dunkle-vergangenheit-die-stadthalle-mal-jenseits-des-guten-und-schoenen.59ab6595-164d-4d60-9df5-c2135e5b0511.html (11.03.2024).

[116] Hartewig 2018, 143.

[117] Christlieb 1960, 218.

[118] Büttner 2011, 59.

[119] Büttner 2011, 64.

[120] Reference 12345 Edith Müller-Ortloff, Meersburg, in: Minutes of the meeting of 10 October 1957, Federal Building Directorate (translated from german), in: BArch Koblenz, B 157 / 90, cited in Büttner 2011, 64 .

[121] Illustrations: Büttner 2011, 63, and Museum der 1000 Orte. Kunst am Bau im Auftrag des Bundes seit 1950, https://www.museum-der-1000-orte.de/kunstwerke/kunstwerk/farbfuge (21/02/2024).

[122] The building was designed by architect Kurt Maenicke (1896-1990), who in 1944 was placed on Joseph Göbbels‘ “ Gottbegnadeten list” of privileged artists of the Nazi state.

[123] In fact, the protruding lip at the openings of the tins bears a strong resemblance to the “Coley” shaker designed by David Wondrich and Greg Boehm based on English models from the turn of the 20th century; see https://cocktailkingdom.com/products/coley-shaker-silver-plated-epns-520ml-18oz (20/03/2024).

[124] The author’s sincere and heartfelt thanks go to Lars Kläschen, the press spokesman of Siemens AG, who provided information on the whereabouts of the Dallinger paintings in three helpful emails in January 2024 and also carried out research at the company’s own art and culture programme on his own initiative.

[125] Christlieb 1960, 219 (translated from german).

[126] Dallinger, Karl Heinrich, in: Nürnberger Künstlerlexikon: Bildende Künstler, Kunsthandwerker, Gelehrte, Sammler, Kulturschaffende und Mäzene vom 12. bis zur Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts, ed. by Manfred H. Grieb, Munich: K. G. Saur 2007, 238; cf. Schmidt 2012, 310.

Abbreviated references

Click here.